Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Element 94 causes a bit of a crisis for our collections.

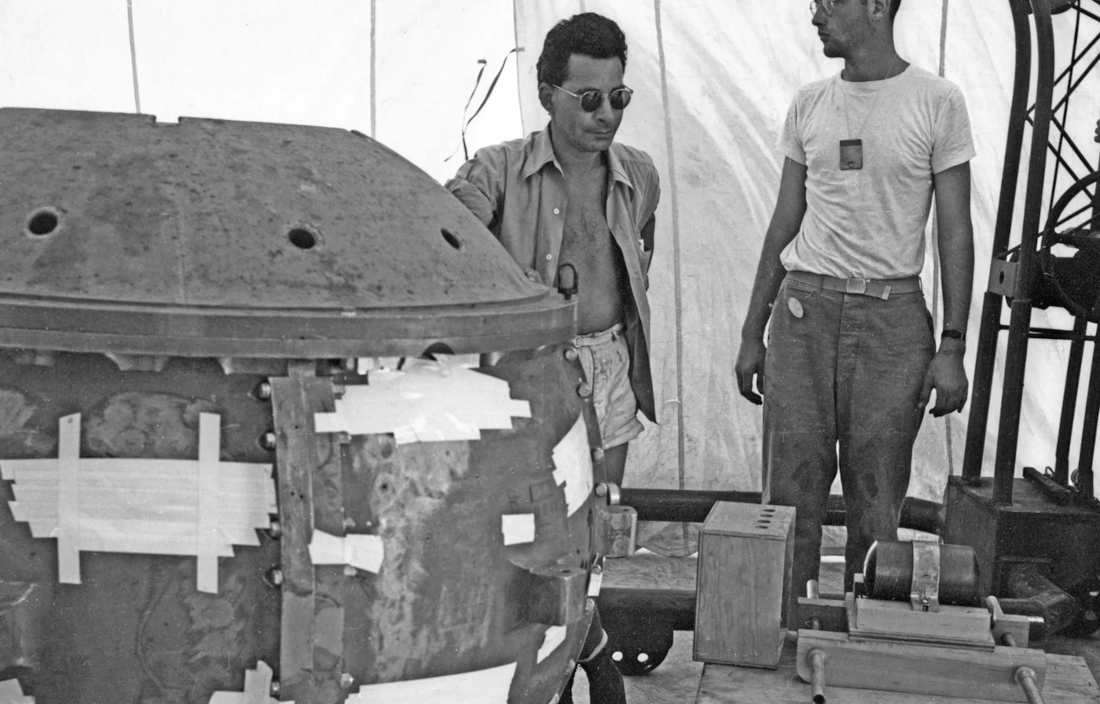

Featured above: Louis Slotin (center) next to the Trinity device, which appears to be held together with lots of masking tape.

Show Notes

Did somebody say Weapons-Grade? Why, that’s the name of that book by friend of the pod Josh Crowley! And wouldn’t you know, he just released his latest iPhone app, Carticulate. It’s a completely original word puzzle game with MS-DOS vibes, and if you enjoy this podcast, you’ll probably have a lot of fun with it. It’s completely free!

Regarding that magical quality plutonium has, I’m not the only one who thinks so (see the image below).

As mentioned at the end of the episode, the discoverers of Pluto and plutonium did meet at least once, although not until long after they made those discoveries. (Those were made in 1930 and 1941, respectively.)

According to Chemical & Engineering News, Clyde W. Tombaugh, the astronomer, finally met Glenn T. Seaborg, the chemist, in 1991, at a colloquium celebrating the 50th anniversary of the discovery of the transuranic elements.

They both died before the year 2000, so neither could have known that Pluto would soon (2006) be welcomed into a new category of heavenly body: the dwarf planet.

Thanks to listener Billy Walsh for tipping me off to this historic meeting!

From watching interviews with Glenn Seaborg, I can tell that he reallly did not have even a trace of the stereotypical Yooper accent. I was fully aware of this and yet performed his voice with that accent regardless. I mean, I’m pretty sure I’m not going to get another chance!

Incidentally, the Voyager probes are still going. I mean, that’s kind of how inertia works, but it’s still cool.

Episode Script

P u! …is the chemical symbol for plutonium, and it’s no coincidence that it sounds like that interjection used in response to foul odors.

Way back in episode 11, we learned the rules for assigning these symbols as outlined by Jons Jacob Berzelius, rules that have remained mostly intact across the centuries. He declared that metals should be symbolized by the first two letters of their name, as long as that didn’t conflict with another element.

Platinum’s chemical symbol is Pt, and palladium’s is Pd, so there was no competition for “Pl” when plutonium was discovered. Why, then, was it assigned this odious initialism instead?

Glenn Seaborg, who led the team that discovered today’s element, just thought it would be kinda funny to give it a symbol that sounded like a kid reacting to a bad smell. He also believed this suggestion would be immediately shot down by the folks in charge — but it caused no kerfuffle at all.1 2

Perhaps the naming committee didn’t notice the juvenile humor — or perhaps they knew plutonium is best left alone.

You’re listening to The Episodic Table Of Elements, and I’m T. R. Appleton. Each episode, we take a look at the fascinating true stories behind one element on the periodic table.

Today, we’re turning up our noses at plutonium.

Plutonium finishes off our elemental triplet referencing heavenly bodies, but its moniker better suits its true underworldly nature. It is one of the most destructive entries on the periodic table, in both practice and potential.

Somewhat surprising, then, that its discovery was relatively quiet and harmless.

Shortly after Edwin McMillan and Philip Abelson proved the existence of neptunium, McMillan was pulled away from Berkeley to help invent radar at MIT.3Powerless to pursue possible postliminary particles produced by neptunium’s progression, his colleague Glenn Seaborg stepped in to continue the search for ever-heavier atoms.4

The team adopted a straightforward approach. Bombarding uranium with neutrons had produced neptunium, so to produce a slightly heavier element, they blasted uranium with particles slightly heavier than neutrons. And it worked! The evidence clearly showed that this process yielded a fresh, hot batch of element 94.

The team was elated. Seaborg himself said, “We felt like shouting our discovery from the rooftop.” Alas, they could not proclaim the good news. The year was 1940, the world was at war, and it seemed clear that this new element would be a valuable strategic resource in some capacity. Recent happenings raised tensions even higher — British intelligence accused the Americans of lacking discretion for announcing neptunium’s discovery to the world just a few months prior. Thus, number 94 became the first chemical element to have news of its discovery suppressed, rather than annunciated.

That secrecy even permeated the lab where Seaborg and company worked. When it was decided that “94” was too obvious a name for the substance, they assigned it an impenetrable code name: “Copper.” Regrettably, copper happens to be a pretty common material in chemistry, so it became known as “honest-to-God copper.”5

The team had a lot of work to do with “copper.” Since they were the only people who even knew plutonium existed, they were the only ones who could advance practical understanding of the atom. Among the top priorities: find out if this new element could fuel an atomic bomb.

Synthesizing trace quantities of plutonium had been a relatively low-risk affair, but now the team was working with macroscopic amounts of the stuff, which required protection from its considerable ionizing radiation. But that wasn’t the kind of lab they worked in — they simply didn’t have the necessary protective gear. That didn’t stop these guys, though. They improvised. Seaborg and his colleagues placed freshly synthesized plutonium in a bucket, which they carried using a long pole and lead-lined gloves. They took the precariously balanced materials across the street to an open-air balcony where they could observe the sample through a hole in a wall they hid behind. Seaborg later recalled, “Gee, you know, it seemed really primitive.”6 7

Primitive or not, their methods revealed that plutonium would actually make an even better bomb than uranium in some respects. And although plutonium’s discovery was kept secret at first, the element made itself known in the most ominous way possible on July 16, 1945, when a plutonium-fueled device became history’s first atomic bomb. Those who did not witness the Trinity test at Alamogordo would bear witness three weeks later, when Americans dropped a similar bomb on the Japanese city of Nagasaki for all the world to see.

The atomic onslaught ended after that detonation, but many officials in the American government had hoped to continue. Mere days after bombing Nagasaki, a brand new plutonium core arrived at Los Alamos, ready to provide the core of another A-bomb. Only Japan’s swift surrender — and an order from President Truman that no more bombs should be dropped without his direct approval — kept it stateside and intact.8

I’m sure this development caused much rejoicing among the eggheads, because that meant they had spare weapons-grade plutonium lying around they could play w– er, conduct experiments upon. They even gave this core a nickname! They called it “Rufus.”

One of those curious minds belonged to 24-year-old Harry Daghlian. He was interested in reducing the amount of plutonium a bomb required by reflecting some of its energy back in upon itself. Working alone one night, he built a wall of neutron-reflective bricks around Rufus. All signs indicated that the experiment was going as planned until it was time to stack the last brick in place. His hand slipped and the brick fell into the plutonium core, triggering an immediate chain reaction. The room was suddenly awash in heat, blue light, and gamma rays.9 10 It only ceased when Daghlian knocked over the bricks using his bare hand.11

He received swift and urgent medical attention, but to no avail. No doctor who treated Daghlian had ever seen radiation poisoning as severe as his. He suffered horrible, painful effects of radiation sickness before slipping into a coma. Twenty-five days after that brick slipped his hand, Harry Daghlian died.

Rufus, however, lived on. It was just a hunk of metal, after all, not a mad dog. New safety protocols were enacted to try to prevent such a tragedy from ever happening again.

A few months later, physicist Louis Slotin wanted to bring the core just to the point of criticality without triggering a chain reaction — similar to what Daghlian died trying to do. This was a demonstration for his colleagues, though, so at least he wasn’t alone in the lab.

Slotin had performed the same procedure many times before, and frankly thought he was pretty hot stuff. In photos from the Trinity test site, he’s the guy wearing a slick pair of shades and fully unbuttoned shirt. For an experiment like this, a cool guy like that didn’t need no stinkin’ safety protocols. He just wedged the plutonium sphere open with a flathead screwdriver and got to work.

You might guess where this is going. At one particularly precarious point, the screwdriver fell from Slotin’s hand. For a second time, the core released a flood of blue light, heat, and gamma radiation. The difference this time was that the room held seven men in addition to the ill-fated experimenter.12

Slotin leapt upon the core to try to shield those men while he pried it apart, ending the chain reaction as quickly as it began. But it was too late, and Slotin knew it. He had visited Daghlian’s bedside, and Slotin knew their fate was now shared. In that moment, he said simply, “Well, that does it.”13 On May 30, 1946, Slotin died in the same room, and from the same cause, as Harry Daghlian.14 15 16 17 18

No one referred to the plutonium core “Rufus” after all that. People started calling it “The Demon Core.” It was melted down and recycled for use in other weapons, so if that plutonium ever hurt another person, it did so under another name.

Plutonium is remarkable for more than just its destructive potential: Its ability to generate electric power, while admittedly niche, is borderline magical. A sizable enough lump of Pu-238 can get very hot — sort of like the nuclear waste we discussed last episode, but much more efficient. Just a handful of the stuff can reach hundreds or even thousands of degrees, and it scarcely matters whether you’re using Fahrenheit, Celsius, or Kelvin.

Heat, as you may know, is energy, and with some clever engineering, thermal energy can be converted to electrical energy. That means basically free energy, from this weird hot rock! Ahhh, okay, I’m sorry, I should be more careful with my words. People tend to get twitchy when you say the words “free energy,” and of course, the rock is only hot because it’s terribly, horribly radioactive.

But… if your use case will be far away from any living thing, and it requires a small amount of energy for a very long time, and solar power and batteries are both unsuitable, then perhaps you need the Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator, also called an RTG for short. The most common use case involves spacecraft exploring the farthest reaches of the solar system. The Pioneer and Voyager probes used RTGs as they escaped the ever-dimming light of our Sun. Several Mars rovers have roamed the planet’s dusty surface powered by RTGs — a fact made famous by Andy Weir’s 2011 novel The Martian (and its film adaptation). Satisfyingly, the New Horizons probe, which visited dwarf planet Pluto in 2015, is powered by a Pu-238 RTG, so yes: plutonium got us to Pluto.19

But RTGs have seen earthbound use, too.

Stretching over thirty-seven thousand kilometers, Russia has one of the longest coastlines in the world.20 There’s a catch, though: Almost all of that coastline is on the Arctic Ocean, which provides poor access to the rest of the world for trade and military purposes.21 Nonetheless, a country has to work with what a country has, so Russia has managed the Northern Sea Route through the Arctic since the 1930s.22 23

The route has some unique navigational challenges that make it far more hazardous than shipping lanes elsewhere in the world. Even as the planet warms, there’s a lot of ice along the route, some of it permanent and some of it seasonal. That can cause some terrible problems — see the 1997 feature film Titanic for further explanation. Specialized icebreakers spend many months out of each year constantly clearing the way for other ships on the Northern Sea Route.

The corridor is also awfully cold, and safe ports along the route are few and far between. In 2021, more than two dozen ships were temporarily stranded among heavy ice, some for as long as six weeks.24

To ameliorate these issues, the Soviet Union built lighthouses and navigation beacons along the Arctic coast. But, again, many of these locations are quite difficult to access. Ideally, these lighthouses would have no need for lighthouse keepers. What better way to keep these unattended, remote lighthouses reliably powered than with radioisotope thermoelectric generators?

So starting in the 1970s, the Soviet government built hundreds upon hundreds of radioactive lighthouses. And apparently, they worked pretty well!… at least, for a while. After a couple decades, many of those RTGs had gone “offline.” Like I said: this is a pretty harsh environment, and these installations were subject to some of the coldest wind, weather, and waves on the planet. The fall of the Soviet government in 1991 didn’t help, either, as that introduced a lot of… organizational disarray.

Additionally, while these lighthouses were difficult to access, they were not impossible. Over the years, many were ransacked by hapless civilians looking for scrap metal they could sell for a tidy profit. Rarely did those scrap hunters realize what an exotic material they were working with. In December 2001, a band of three such opportunists from the country of Georgia were especially unfortunate.

The anonymous men had driven out to the woods to gather firewood, where they stumbled upon something incredible: a couple of metal cylinders that had melted all the snow nearby, even causing the wet ground to steam. When one of the individuals attempted to grab one of the cylinders, it was so hot that he immediately dropped it.

Coincidentally, it was starting to get late, so the men decided they’d make camp for the night and head back in the morning. It must have seemed like quite a stroke of luck that they had discovered these inexplicable heat sources, which kept them toasty while they ate dinner and drank a little vodka under the stars.

What you know that they didn’t is that they were warming their feet by the heat of a couple of RTGs. These used to power a Soviet radio beacon, but had long ago lost their frames, heat fins, and anything else that might provide shielding from the potent source of radiation within. Within a few hours, the men began to fall ill. They were completely unable to sleep, partly because they spent all night profusely vomiting instead. When morning came, they were too exhausted to load more than half their collected firewood into their truck, and they drove back home.25

They left the RTGs in the woods, but their symptoms did not improve. All three had to be hospitalized, eventually undergoing years of intensive medical treatment. Even after receiving care from some of the most qualified doctors in the world, one of the three succumbed to multiple organ failure in May 2004.

This tragic tale happens to be an unusually well documented incident. Many other RTGs are known to have been stolen, but many of them have gone missing for unknown reasons — and no one is entirely sure just how many of them were ever put out there in the first place.26 27 International efforts have managed to decommission hundreds of the generators, but that work came to a halt following the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014.28 As of 2022, the official line from the Russian government is that they’ve managed to recover every last one.29 30 31

I should mention that Russia’s terrestrial RTGs did not actually contain any plutonium. They operated on the same principle, but instead used strontium-90. That isotope has a shorter half-life, but will still get the job done — and for a fraction of the cost.

However, for a little while, there was an application of plutonium power that literally could not have been closer to ordinary members of the public.

In episode 45, we heard the fascinating history of the pacemaker, the implantable medical device that helps keep a patient’s heart beating. The invention of said device predates the invention of efficient, long-lasting batteries, though, so early versions were sometimes supplied electricity in surprising style. In episode 61, we learned that some pacemakers were powered by promethium, but that sounds downright adorable compared to a competing technology.

You guessed it: one early pacemaker contained a core of plutonium-238.32 Like most iterations of the implanted implement, it was buried within a person’s chest, millimeters away from their heart and lungs.

Well, not always a person. In 1969, a beagle named Brunhilda — whom I can only presume was a very good girl — became the world’s very first recipient of a P u p m.33 Less than a year later, a 58-year-old French woman became the first human to undergo the same procedure.34 35

These devices worked in essentially the same way as the RTGs discussed earlier. Radioactive decay released heat, which was then converted to electrical energy.36

The idea wasn’t actually as ridiculous as it probably sounds. For starters, Pu-238 primarily emits alpha particles, which are easy to block.37 38 By surrounding the power source with effective shielding, a patient’s radiation exposure was kept to the rough equivalent of one full-body CT scan every year.39

These things were sturdy, too. The designers knew they were dealing with a uniquely hazardous and valuable material, so they made sure their product could withstand all sorts of abuse — up to and including gunshots.

Plutonium pacemakers had some advantages over existing technology, too. In 1970, a typical implant would only last about a year and a half before needing replacement. One notable patient had received ten pacemakers in ten years.40 The zinc-mercury battery had a tendency to leak fluid into the implant’s housing, causing a sudden failure.41

In comparison, the nuclear model was designed to last a full decade before wearing out, greatly reducing the cost, stress, and danger of being a person with a pacemaker.Ten years turned out to be a pretty conservative estimate, too. The plutonium implants frequently lasted twice as long, and some lasted more than thirty years without a problem.42From 1970 to 1989, an estimated three thousand patients received plutonium-powered pacemakers.43 44And by all metrics, they worked splendidly! Those patients experienced better outcomes than those who received non-nuclear models, and there are no known cases of the devices leading to radiation incidents.”Well,” you might ask, “if these things are so great, why’d they stop making them?” Excellent question, listener! Advances in battery technology eventually led to non-radioactive pacemakers that could last just as long for a much lower cost. Also, governments were never totally comfortable with that much plutonium being released into the wild. And even though the devices were impressively safe for patients, they could become more dangerous for everyone else upon a patient’s expiration.If a deceased patient were to be cremated without first removing their pacemaker, the isotopes inside would be immolated, too, potentially harming the mortician, the crematorium, and the surrounding environment. In light of these issues, the risk — and the price — was deemed too great. No one has been granted an atomic heart since the 1980s, so if any plutonium-powered pacemaker patients persist in the year 2025, they are very rare indeed.45That makes you unlikely to add element 94 to your element collection this way, unless you are a very lucky, thorough, and unscrupulous undertaker.The fellas at Los Alamos National Labs are also unlikely to help you procure a sample, no matter how politely you request one. In fact, they’re more likely to hunt you down.That’s because Los Alamos runs the Off-Site Source Recovery Program, whose mission is to find and remove “excess, unwanted, or disused US-origin radioactive sealed sources that pose a potential risk to national security.”46 A civilian stash of off-the-books plutonium would definitely earn their attention, and your sample might join more than forty-four thousand others the program has recovered since 1997.47There is at least one element collector who managed to turn the tables on the OSRP. In March 2017, a pair of specialists with the program picked up plutonium and radioactive cesium from a nonprofit research facility in San Antonio, Texas.48 Before heading back to Idaho National Laboratory, they booked a room at a local Marriott… and left their tools and radioactive spoils in the back of their rented SUV.The next morning, they found the car’s window had been smashed and the element samples had been re-reclaimed. More than a year later, the U.S. government still had no idea where they had gone.

So it might be possible to get one over on the chemistry police, but that would involve partaking in unquestionably criminal activity — the kind of action that this program explicitly discourages. Aside from the burglary, any Americans found guilty of possessing plutonium “without lawful authority” face steep penalties, including hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines and prison time up to and including a life sentence.49

The problem, at least from our perspective, is that there is effectively no way for a proletarian element collector to earn the “lawful authority” to acquire plutonium. Without extensive credentials and a very good reason, no government in the world allows unfettered access to this highly radioactive fuel for weapons of mass destruction.

However, dear listener, perhaps we can choose to see this as an opportunity rather than a hindrance. I invite you to do something truly radical and leave slot 94 deliberately empty on your presentation of the elements. Perhaps this spot can provide a moment’s rest on our molecular marathon. Perhaps the viewer will notice that the collection they behold is something wrought with human hands. We are not automatons, slavishly enacting some higher order. No, we possess the wisdom to recognize that some things are simply too dangerous to possess, and so we abstain. Yea, plutonium is absent from this display not because I could not acquire it, but because I knew I should not acquire it, and thus, would not acquire it.

And if, upon taking such a principled stance, you no longer need to worry about acquiring a deadly substance while skirting strict and complicated laws, well… that’s just an added bonus.

Thanks for listening to The Episodic Table of Elements. Music is by Kai Engel. To learn about the time the discoverer of plutonium met the discoverer of Pluto, visit episodic table dot com slash P u.

Next time, we’ll return to our home planet with americium.

Until then, this is T. R. Appleton, reminding you to adhere to any rules and safety regulations when conducting experiments — no matter how cool you are.

Sources

- Berkeley Lab Science Beat, Glenn Seaborg: A Man In Full. Lynn Yarris, March 5, 1999.

- FRONTLINE, Nuclear Reaction: Why Do Americans Fear Nuclear Power? Interview with Glenn Seaborg.

- Los Alamos Science, Reflections On The Legacy Of A Legend. David L. Clark and David E. Hobart, 2000.

- Los Alamost National Laboratory Actinide Research Quarterly, A History Of Plutonium. Owen Summerscales, September 21, 2022.

- The Elements Beyond Uranium, p. 14. Glenn T. Seaborg and Walter D. Loveland, 1990.

- Mystery Of Matter: Search For The Elements, p. 26. Script from 2015 documentary.

- Los Alamost National Laboratory Actinide Research Quarterly, A History Of Plutonium. Owen Summerscales, September 21, 2022.

- Outrider, The Third Shot. September 7, 2018.

- Linda Hall Library Scientist Of The Day, Harry Daghlian. September 16, 2022.

- How Stuff Works, The Demon Core: A Tale Of Atomic Ambition And Tragic Fate. Clarissa Mitton, April 3, 2024.

- Atomic Heritage Foundation, Harry Daghlian. 2022.

- CBC, Louis Slotin And The Demon Core: Winnipeg’s Oppenheimer Connection. Darren Bernhardt, July 29, 2023.

- An Albuquerque Journal Special Reprint, Nuclear Naiveté. Larry Calloway, July 1995.

- Atomic Heritage Foundation, The Dragon Bites Twice: “Tickling The Tail Of The Dragon”. June 4, 2014.

- sci-ed.org, Tickling The Dragon’s Tail. Stephen Klassen, September 2015.

- The American Physical Society, This Month In Physics History: May 21, 1946: Louis Slotin Becomes Second Victim Of “Demon Core”.

- CBC, Louis Slotin And The Demon Core: Winnipeg’s Oppenheimer Connection. Darren Bernhardt, July 28, 2023.

- The New Yorker, The Demon Core And The Strange Death Of Louis Slotin. Alex Wellerstein, May 21, 2016.

- New Horizons: Reconnaissance Of The Pluto-Charon System And The Kuiper Belt, p. 39. C. T. Russell, 2009.

- CIA World Factbook, Coastline.

- The Atlantic, Russia And The Curse Of Geography. Tim Marshall, October 31, 2015.

- Proceedings, Soviet Strategic Interest In The Maritime Arctic. Captain Gerald E. Synhorst, May 1973.

- The Arctic Institute, Geopolitical Implications Of New Arctic Shipping Lanes. Gabriella Gricius, March 18, 2021.

- High North News, Unusually Thick Sea Ice To Make For Challenging Shipping On Northern Sea Route This Summer. Malte Humpert, March 8, 2023.

- International Atomic Energy Agency, The Radiological Accident In Lia, Georgia. (PDF) December 2014.

- Nuclear Threat Initiative, Radiological Materials In Russia. Christina Chuen, June 30, 2004.

- Bellona, Nuclear Lighthouses To Be Replaced. Thomas Nilsen, February 2, 2003.

- Jalopnik, USSR Sprinkled More Than 2,500 Nuclear Generators Across The Countryside. Erin Marquis, June 16, 2023.

- Bellona, Foreign Funds Have Almost Entirely Rid Russia Of Orphaned Radioactive Power Generators. Charles Digges, November 12, 2015.

- Bellona, Two Strontium Powered Lighthouses Vandalised On The Kola Peninsula. Igor Kudrik, November 17, 2003.

- BBC, The Nuclear Lighthouses Built By The Soviets In The Arctic. Irina Sedunova, Anna Pazos and Anna Bressanin, February 23, 2022.

- The Wall Street Journal, How Do You Handle A Plutonium-Powered Pacemaker? Becky Yerak, January 17, 2022.

- Brookhaven Bulletin, Atom-Powered Heart Pacemaker Now Used. June 12, 1969.

- The New York Times, A Heart Is Given Atom Pacemaker. John L. Hess, April 29, 1970.

- Nuclear Newswire, The Case Of The Pu-Powered Pacemaker. January 20, 2022.

- Medical Justice, Your Patient Has A Plutonium Powered Pacemaker. Anything To Know? Jeffrey Segal, January 23, 2022.

- United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Backgrounder On Plutonium. Last updated January 7, 2021.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, Radiation Basics.

- U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Doses In Our Daily Lives. Last updated April 26, 2022.

- The New York Times, Nine Nuclear Heart Pacemakers Implanted. Harold M. Schmeck, Jr., April 10, 1973.

-

Mallela VS, Ilankumaran V, Rao NS. Trends In Cardiac Pacemaker Batteries. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2004 Oct 1;4(4):201-12. PMID: 16943934; PMCID: PMC1502062.

- Reuters, Nuclear Pacemaker Still Energized After 34 Years. December 19, 2007.

- CHAUVEL, C., LAVERGNE, T., COHEN, A., DUCIMETIERE, P., YVES le HEUZEY, J., VALTY, J., & GUIZE, L. (1995). Radioisotopic Pacemaker: Long-Term Clinical Results. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 18(2), 286–292. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.1995.tb02518.x

- PACE, Thirty-One Years Of Clinical Experience With “Nuclear-Powered” Pacemakers. Victor Parsonnet, Jack Driller, Debra Cook, and Syed A. Rizvi, February 2006.

- Archives Of Cardiovascular Disease Supplements, This Is The End. S. Boulé and C. Kouakam, January 2018.

- Los Alamos National Lab, Off-Site Source Recovery Program, OSRP.

- LANL Off-Site Source Recovery Program, OSRP Recoveries To Date. As of February 5, 2025.

- The Center For Public Integrity, Plutonium Is Missing, But The Government Says Nothing. Patrick Malone and R. Jeffrey Smith, last updated July 20, 2018.

- 18 USC Chapter 39, Explosives And Other Dangerous Articles.

Loved it! Thank you, TR Appleton!

I believe if you were a truly unscrupulous element collector, there are a couple of old Russian smoke detectors that contain relatively small amounts of plutonium.

Now this is exciting to learn!

Huh, I knew some smoke detectors contain Americium, but I didn’t know other radioactive elements had gone into making them.

Yay! This is one of my favorite podcasts.

I’m on my fourth listen through of this podcast, pleasantly drifting through the lanthanides yet again.. but I have no self control and had to jump right into Plutonium!

Superb work as always Mr. Appleton 👍🇨🇦

Your hard work and numerous accents are always entertaining, educational and much appreciated in these insane times. Xo 🇨🇦

Thomas, perhaps instead of leaving slot Pu empty some safe and yet relevant artefacts could be 2008 New Mexico State Quarter

Coin / 1962 4c New Mexico Statehood Stamp / 2019 USA Forever Stamp “Mountains and Yucca” / 2002 37c Stamp Greetings

from America: New Mexico. Alternatively there are Washington State Coin 2007, Washington Statehood Stamp 1989 & Washington

State Stamp 1976 all relating to Hanford, WA.

I absolutely love The Episodic Table of Elements! Such a brilliant idea, beautifully executed. I started listening about two years ago, and while I haven’t gone through all the episodes, I’ve listened (and re-listened) to many of them. I’ve recommended it to several colleagues, family, and students, and I’m pretty sure at least a couple of them actually listened to it.

Your podcast has also inspired me to create a few collaborative art projects with my middle school students, like a wall-sized periodic table and a giant “Adventskalender” with element samples in liu of sweets behind each door. Now it’s almost time for our intro to chemistry unit (the most wonderful time of the school year!), and I’m ready to overwhelm my poor 7th graders with even more periodic table projects—lol.

Thank you so much for putting this wonderful work together. I hope you continue releasing new episodes –even if just periodically!

It’s an honor to hear that an educator enjoys the program, let alone has gone on to create such exciting projects with their students. I’d love to see or hear more about any of those! Good luck with your intro to chemistry — it sounds like your 7th graders are in excellent hands! Thank you so much for your comment, Alejandra, and for being a listener!