Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Sometimes we need a quiet moment in order to step back and look at the bigger picture.

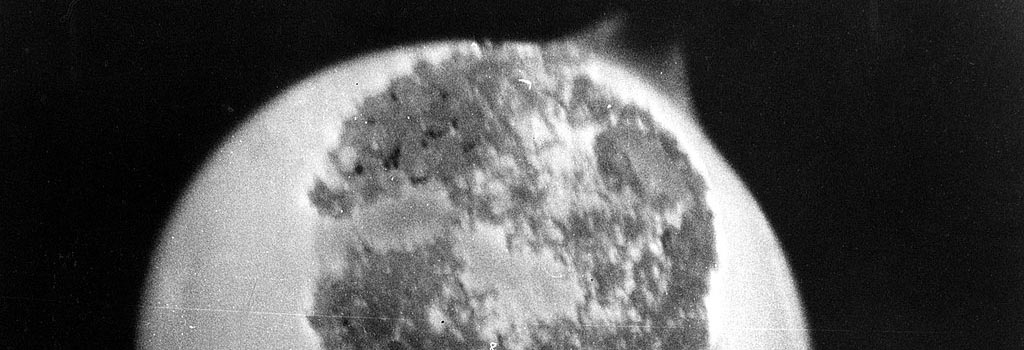

Featured above: A detail of a photograph of protactinium lit by its own radiation. See below for the full image.

Show Notes

I’m actually not entirely sure that my stance on each element getting a single episode was stated, but, well, now it is.

Between the assertion that it’s boring, and the focus on non-Eurocentric science, this episode is a bit of a spiritual successor to Zinc.

I’ve included a surfeit of sources below, but here’s some extra reading that didn’t directly contribute to the script. Still a very interesting and informative read, though: How Decolonization Could Reshape South African Science.

Slightly worth mentioning that some scientists have been considerably intrigued by protactinium. For instance, H. W. Kirby, a scientist at Monsanto in 1959. He was interested in the “mystery and witchcraft” that surrounded the element.

Previous episodes have noted that the boundary between chemistry and alchemy is blurrier than we sometimes think. Anyone performing chemistry in the 16th century was standing on the shoulders of alchemical giants. For several hundred years, the study of matter was centered in Southwest Asia and North Africa. Just because the alchemists lacked knowledge of atomic theory doesn’t mean they contributed nothing to the body of scientific discoveries. Their influence is apparent in the language that we use even today: alkali, soda, muriatic acid, nitrate, and many others are words that come from Arabic and Egyptian alchemists — based on knowledge that sometimes traveled from much farther south or east.

“Race science” in particular is a contradiction in terms, since “race” is a concept with absolutely no scientific meaning whatsoever. (Unless we’re talking about the race between Achilles and the Tortoise, and even that’s a stretch.)

And here’s the full version of that photograph. It comes from the US Department of Energy, as described from the caption on Wikipedia: This sample of Protactinium-233 (dark circular area in the photo) was photographed in the light from its own radioactive emission (the lighter area) at the National Reactor Testing Station in Idaho.

Greetings, listener! If you’re listening to these episodes as they’re being released, you might have noticed that it’s been a while.

I lament the delay.

There are many reasons why I haven’t released an episode in so long, but there’s one that’s especially relevant today: It’s very difficult to write an episode about an element that’s so boring. It’s scientifically proven, in fact, that protactinium is the most boring element, per a July 2019 issue of Nature.1

And yet, here we are. So is that official scientific assessment accurate? Only one way to find out.

You’re listening to The Episodic Table Of Elements, and I’m T. R. Appleton. Each episode, we take a look at the fascinating true stories behind one element on the periodic table.

Today, we’re testing protactinium.

It is the stated belief of this podcast that every element is interesting enough to warrant precisely one episode. No combinations, no multi-parters. Do I recant this bold stance?

Here’s the conundrum: There is plenty of history involving protactinium. The problem — for us, at least — is that it tends to be history we’ve already covered, or history that rightly belongs to future episodes.

To wit: Dmitri Mendeleev predicted the existence of element 91 in one of his early periodic tables — but he predicted the existence of several elements, and we’ve talked about that several times before.2

Protactinium weighs less than the element right before it, one of four such “pair reversals” on the periodic table. That is genuinely unusual — but we already talked about that in the episode on promethium, and even earlier in the show notes for argon.

Protactinium’s history is one of multiple discovery — the kind we’ve heard in many previous episodes — but there is an interesting twist. Kasimir Fajans and Otto Göhring discovered an isotope of protactinium in 1913. It had a half-life of only a few hours, so Fajans wanted to call it “brevium.” You know, like brevity, brief. A few years later, Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn discovered a much longer-lived version, with a half-life of more than 30,000 years. Apparently there was a custom at the time that, in a case like this, whoever discovered the most stable isotope earned the right to name the element. Thus, “brevium” was out, and “proto-actinium” was in. (It’s kind of a pain to say “proto-actinium,” so, subject to the erosive forces of spoken language, that second “o” eventually disappeared, leaving us with “prot-actinium.”)3 4

Hahn and Meitner are some of the most interesting characters in the history of chemistry — but really, we should save their story for meitnerium, the element named after Lise.

But we are not completely bereft of material here. This actually gives us a prime opportunity to zoom out a bit and look at a trend you may have noticed among all the elements, and not really unique to any one of them. Nonetheless, it’s important to discuss. I’m referring to a certain trend among the historical figures we talk about in every episode.

Meitner, Mendeleev, Lavoisier, Berzelius, von Welsbach, Rutherford, Davy… We spend a lot of time talking about white people, is what I’m saying. Usually white men. Some might say a disproportionate amount of white men are present in the history of science.

When our gaze does shift toward Central and South America, Africa, Australia, and Asia, it’s almost always in the context of what western nations did to those places. Why is that?

It’s certainly not because of an inherent superiority of white men, some scientific acumen that’s solely accessible to European males. Rather, it comes down to one very basic question that often goes unasked: “Who gets to do science?”

Throughout most of history, science has been a self-funded activity. There are some notable exceptions — rulers of the late Mayan civilization funded extensive research in astronomy and mathematics, for instance,5

6 and scientific grants have been around for a couple hundred years now — but usually, study of the natural world has been practiced by those who could afford to do so.7 8

That means laboratory space with expensive equipment, sure, but it’s more than that: Who could afford to spend their time faffing about with rocks and bugs and things, rather than laboring to support their families? Who could afford the kind of education required for such studies?

Even when scientific institutions started to spring up in Europe, they rarely distributed the social burden of educating the populace. Instead they often went in the other direction, explicitly restricting admissions based on race, gender, and class.9 Recall that even our man Mendeleev was rejected from the University of Moscow because he hailed from Siberia.10

Science history in general, and this program in particular, tend to focus on a relatively recent period; the past five centuries-ish. It is no coincidence that the same period saw the first voyages to the Americas; the founding of the various East India Trading Companies; the Scramble for Africa; the Stolen Generations; and other atrocities too numerous to mention. White men have held an unparalleled grip on global power in that time, and that power has come at the great expense of the rest of the world. A land that’s been drained of its natural resources and human population is poorly situated to make elemental discoveries, to put it lightly. The history of science cannot be separated from the history of imperialism.11 12

Occasionally, that great power was used to erase scientific knowledge held by the oppressed. For example, in the 18th century, plantation owners discovered that an enslaved Jamaican was gathering a particular kind of plant. Paranoid that the plant would be used as a poison against them, the slaveholders quickly decided to lynch the man.13

Except, oops, the Europeans soon figured out that this plant happened to have a wide range of medicinal uses. It became renowned among the colonizers as a remedy for worms, warts, and more. Thus was indigenous knowledge erased and another discovery attributed to European scientists.

The relationship works in both directions. Western science didn’t simply benefit from the loot and plunder of the rest of the globe, but scientific advances directly enabled imperial powers to conquer more efficiently.

Ronald Ross explained this quite succinctly in December 1899, when he wrote, “In the coming century, the success of imperialism will depend largely upon success with the microscope.”14 Ross was a doctor, you see, and he made discoveries to help treat malaria — a disease that was more likely to affect white occupiers than indigenous people, since the latter had a greater natural resistance. Healthier colonizers meant more colonization.15

Elsewhere in time and space, Christiaan Huygens and Gian Domenico Cassini conducted astronomy research to help pinpoint the location of St. Domingue… in order to allow the more efficient delivery of slaves.

Infamously, anthropological studies often helped justify beliefs and practices that we now rightly see as wildly racist, and such pseudoscientific studies proliferated because they reinforced the wildly racist beliefs that white people already held. For instance, categorizing the various peoples of the world by relating the shape and size of their skull to their inherent intelligence. Decades of absolutely meritless pro-eugenics arguments were made in the name of “science,” and honestly, we still haven’t rid ourselves of those people.16

These are just a few of the endless examples of research enabling the subjugation of nonwhite people. But the sciences grapple with the legacy of colonialism in other ways, too.

People of color remain grossly underrepresented in the sciences, subject to a variety of discriminatory policies and attitudes that can be directly traced to the colonial era. Barriers to entry keep people of color out of academia,17 18 19and those who do break through are often harassed out of academia.20 21

And to be sure, racism need not always be overt. A 2019 study concluded, “Universities are failing to create environments where … race and racial inequality is discussed competently, confidently, and constructively.”22 When institutions fail to address existing systems of inequality, they de facto reinforce those systems of inequality. (I will, as always, provide sources in the show notes.)

Despite many obstacles to progress, past and present, nonwhite people have made broad and significant contributions to science. But, in another cruel twist, those contributions are highly likely to go unacknowledged.23

As much as 80% of research conducted in Central Africa is done by scientists from places other than Central Africa — often from the same nations who had occupied Central Africa a century before. Local scientists are usually assigned to assist those foreign scientists, rather than carry out independent research — and when those foreign scientists publish research, as many as 70% of them fail to include their local collaborators as co-authors on their papers.24

This is not just a problem of publication, but also one of education. For instance, George Washington Carver was an unparalleled pioneer of agricultural science and a prolific inventor, creating soy-based fuels; cheap and portable soil laboratories; substitutes for rubber and dyes; and so much more. Even more remarkably, he saw science as a pathway to Black autonomy. Born into slavery in the 1860s, he spent his life helping fellow Black Americans become self-sufficient through affordable and sustainable farming methods.

(Oh, and incidentally, the “Washington” is a nod to his mentor and friend Booker T. Washington, not President George Washington.)25

Carver might be American history’s most famous black scientist, especially since he’s oft discussed in elementary schools during Black History Month. But how many of us learned anything about Carver other than, “something something, peanut butter, something something”? I certainly didn’t. (And just for the record, while Carver worked a lot with peanuts, he did not invent peanut butter, nor did he ever claim to.)

So consider the unsung contributions of food scientist Marie Maynard Daly, biochemist Alice Ball; chemical engineer Norbert Rillieux; industrial research chemist Bettye Washington Greene; and countless other POC scientists who were never admitted to our classrooms.26

I try to highlight the achievements of nonwhite, nonmale scientists whenever possible, but I could certainly do better. On this program, I talk about so many dead white guys, often with the help of histories written by other white guys, and I myself am another white guy. It’s hard work to push back against centuries of bigotry, and none of us succeeds all the time. Nevertheless, the work must be done.

That work is starting to fall under the banner of “Decolonizing Science” — all the things that must be done to counteract the centuries of white supremacy entangled with our study of the material world.27 28 29

Science is not an objective lens through which we view the world, and it is not a cloak that magically deflects criticism. At its best, it is an approach, an attitude, invented and adopted by humans and subject to all the same flaws as our human brains. If we endeavor to be scientific, then we cannot deny our biases. Instead we must acknowledge them, to ourselves and within our work, and then we must competently, confidently, and constructively counteract them.

We’ll never discover the beauty and wonder of the periodic table if we insist that everything is made of earth, air, fire, and water.

Of course, I know that you are a person who is pursuing the real chemical elements of the universe in the best of faith. Unfortunately, the options for acquiring element 91 are rather limited. In fact, when it comes to adding protactinium to your element collection, we bump into the same problem we had with today’s narrative: The most relevant information rightly belongs in another episode.

That’s because when protactinium occurs in the domicile, it’s practically always because it’s the decay product of another element. Protactinium’s presence is a mere side effect, nothing intentional, so it feels a little improper to poach that information for today’s episode. Let’s just tuck away this little nugget of information and recall it four episodes from now.

Protactinium does occur as part of several different decay chains, actually, so you might also get your hands on it by way of thorium, uranium, or plutonium. It’s rather difficult to acquire the isotopes that undergo that particular process, though, and you wouldn’t want some of those in your home, anyway.

Minute traces of protactinium can be found in samples of ocean sediment, and actually offer a way to date the origin of those samples — but, once again, that’s the kind of process we’ve spoken about before, especially in episode 6, Carbon.

So that’s basically collection for you. But before we close out the episode, there is something about element 91 I should level with you about: That Nature article that proclaimed protactinium is the most boring element. That’s not exactly what happened there.

After systematically investigating every element on the periodic table, clocking it for interest, the authors settled at last upon protactinium. They mentioned its occurrence in certain decay chains. “Oh, and it’s pretty rare,” they write. “And that’s about it, as far as we can find.”

But then, they waffle in the final paragraph, saying that protactinium is not boring to someone who studies protactinium. There are people who study protactinium, thus and so, therefore ergo, hence and such ipso facto, it cannot be boring. “We should be reveling in the astonishing diversity of all the elements,” they conclude, “there’s not a boring one among them.”

Well then. I suppose that I’m left with little excuse for my tardiness, but at least we can agree on what’s really important.

Thanks for listening to the Episodic Table Of Elements. Music is by Kai Engel.

To see a photograph of protactinium bathed in the light of its own radioactivity, and to find many more notes on the link between science and imperialism, visit episodic table dot com slash p a.

I am very pleased to finally release this long-awaited episode. My genuine thanks to all of you who sent kind, patient messages; left a review; or simply waited without giving me the evil eye. I try to respond to everyone who reaches out, but I apologize if I didn’t get back to you.

I’ve been champing at the bit30 to get back to a regular release schedule. However, we have the opposite problem with the next episode: There’s so much to say that it will be hard to choose what not to include. So I beg your continued patience while I research that most critical element, uranium.

Until then, this is T. R. Appleton, reminding you that George Washington Carver “could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.”31

Sources

- The Most Boring Chemical Element, Rebecca E. Jelley and Allan G. Blackman. Nature Chemistry, July 29, 2019.

- Chemistry In Its Element: Protactinium. The Royal Society Of Chemistry.

- FAJANS, K., & MORRIS, D. F. C. (1973). Discovery and Naming of the Isotopes of Element 91. Nature, 244(5412), 137–138. doi:10.1038/244137a0

- Nature, In Your Element: Peculiar Protactinium. Richard Wilson, July 2012.

- Journal Of Astronomy In Culture, Discovering Discovery: Chich’en Itza, The Dresden Codex Venus Table And 10th Century Mayan Astronomical Innovation. Gerardo Aldana, 2016.

- LiveScience, The Maya Were Tracking The Planets Long Before Copernicus. Tia Ghose, August 22, 2016.

- The Brink, Who Picks Up The Tab For Science? Art Jahnke, April 6, 2015.

- Wiley, An Illustrated History Of Science Funding. July 21, 2017.

- Schiebinger, L. (1990). The Anatomy of Difference: Race and Sex in Eighteenth-Century Science. Eighteenth-Century Studies, 23(4), 387. doi:10.2307/2739176

- See Episode 0!

- Imperialism and Science

Author(s): M. Anis Alam

Source: Social Scientist, Vol. 6, No. 5 (Dec., 1977), pp. 3-15

Published by: Social Scientist - PNAS Perspective, Anthropology, Inequality In Science And The Case For A New Agenda. Joseph L. Graves, Jr., February 24, 2022.

- The Conversation, Decolonise Science — Time To End Another Imperial Era. Rohan Deb Roy, April 5, 2018.

- Smithsonian Magazine, Science Still Bears The Fingerprints Of Colonialism. Rohan Deb Roy, April 9, 2018.

- Malarial Subjects: Empire, Medicine And Nonhumans In British India, 1820-1909. R. Deb Roy, September 2017.

- The Anatomy of Difference: Race and Sex in Eighteenth-Century Science

Author(s): Londa Schiebinger

Source: Eighteenth-Century Studies, Vol. 23, No. 4, Special Issue: The Politics of Difference

(Summer, 1990), pp. 387-405

Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press. Sponsor: American Society for Eighteenth-

Century Studies (ASECS). - The Royal Society, A Picture Of The UK Scientific Workforce. 2014.

- Universities UK, Black, Asian, And Minority Ethnic Student Attainment At UK Universities. May 2019.

- Chemistry World, UK Chemistry Pipeline Loses Almost All Of Its BAME Students After Undergraduate Studies. Katrina Kramer, August 10, 2020.

- Tackling Racial Harassment: Universities Challenged, p. 94. Equality And Human Rights Commission, 2019.

- Equality And Human Rights Commission, Racial Harassment Inquiry: Survey Of University Students. October 2019.

- ibid.

- The Washington Post, References To White Men Still Dominate College Biology Textbooks, Survey Says. Bethany Brookshire, July 26, 2020.

- Scientometrics, Neo-Colonial Science By The Most Industrialised Upon The Least Developed Countries In Peer-Reviewed Publishing. Farid Dahdouh-Guebas, J. Ahimbisibwe, Rita van Moll, Nico Koedam, 2003.

- History.com, George Washington Carver. Last updated August 29, 2022.

- Nature Chemistry, The Missing Colors Of Chemistry. Binuraj R. K. Menon, January 29, 2021.

- University Of York Department Of Chemistry, Decolonizing Chemistry.

- The Conversation, Five Shifts To Decolonize Ecological Science — Or Any Field Of Knowledge. Jess Auerbach, Christopher Trisos, and Madhusudan Katti, July 5, 2021.

- Decolonizing The Undergraduate Chemistry Curriculum: How To Start.

J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99, 1, 5–9

Publication Date:October 18, 2021

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.1c00397

Copyright © 2021 American Chemical Society and Division of Chemical Education, Inc. - Yes, this is a correct way to say the phrase. But as always, I’m no linguistic prescriptivist. Chomp away at that bit all you please, I’ll still know what you mean.

- Directly from the good scientist’s epitaph.

“Boring” cannot squish through the filter of T. R. Appleton. Your stepping back to look at science and scientists is a celebratory step forward in brilliant entertaining education.

You’re too kind! I’m so glad you enjoyed the episode.

I LOVE this podcast. I hope you finish the table!

Great to have you back Sir, I’ve missed my episodic fix.

I hope you are well and look forward to the next instalment, I don’t envy your task of editing it down though.

Kind regards Martyn

And I’m so glad that you’re back as a listener, too.

“Boring?” On the contrary, I was unbelievably excited to see this episode pop up in my updates this morning! So glad you’re back. Hope all is well.

Why thank you so much! I’m glad to be back.

I’m so happy to learn that you’re back publishing episodes! Hopefully the next one will be a banger. (Yes, that pun was intended.)

It’s gonna be lit! 😂

I almost didn’t believe it when I repetedly pressed 2 to get down to the post navigation heading and tabbed pas the link to sorry for the inconvenience to land, not on a social media link, but on a link to a new post, especially since its Thursday.

Can’t wait to listen to the new episode. I feel like I’m waiting for the premier of the first new episode of of a much beloved favorite I just heard got uncancelled.

I almost couldn’t believe that I actually finished the episode! Hope you enjoyed, and thanks for coming back to say hi. 🙂

You have no idea how excited I am to see this episode. I have been listening to the series on repeat, and was so surprised when this popped up instead of Hydrogen. So glad you’re back.

Thank you so much! It brings me a lot of joy to know there are folks out there looking forward to the episodes. I’m hoping to keep the momentum going!

I was really looking forward to this posting, nice to see you are back. Are there any links to your the piano music? Thanks for continuing this endeavor. I wish others could grasp the professional level of podcasts. Maybe you just set the bar too high

Thank you for your kind words, and for listening! Regarding the piano music, almost all the music in every episode is by a musician named Kai Engel. You can hear more of his work here: https://kaiengel.bandcamp.com

He’s actually released a lot of new music lately, but I can’t use it in the show since it’s released under a different license.

Welcome back, you have been missed.

You managed to make an interesting and culturally relevant topic out of this episode! An element without many unique stories to tell is a good opportunity to discuss real-world problems that prevail today. Such is exactly the problem I have with things like Black History Month: it makes celebrating the accomplishments of an enormous subset of humans feel like an annual obligation to do 28 days at a time.

“Something something peanut butter”, unfortunately, is all I can recall learning about George Washington Carver in school.

Great news that you are back and what a special episode but so different, looking forward to Uranium, will be awesome, welcome back and hope you are getting better

Recently discovered the podcast and love it! Please sir, may we have some more?

The same problem happens with technology today; with the Big Tech companies doing neocolonialism on third world countries. Thankfully we have open source to help.

P.S is this why Japan had no element discoveries until 2003?

Hello, I’m waiting for element 92 and the rest ;-). What’s happening? I cannot find it. Please do not give up.

I’m not giving up! I’m just very, very slow. Element 92 is actually coming soon, though: https://episodictable.com/something-rather-than-nothing/

My apologies for the delay in responding and in releasing episodes!

And it looks like that it’s the last element to be named after another element so far.

T.R. a unique Numisbrief of Otto Hahn & Lise Meitner was issued by Germany (BDR) on the 12th Aug 1989, this contained a coin dedicated to Hahn & a stamp dedicated to Meitner. Thus even the Uncollectable Pa is “collectable”.

Very cool, that’s a great tip!

The most boring element.. how very interesting that is.