Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Chlorine is an element that causes some extreme reactions, and occasionally inspires some pretty extreme reactions in humans, too.

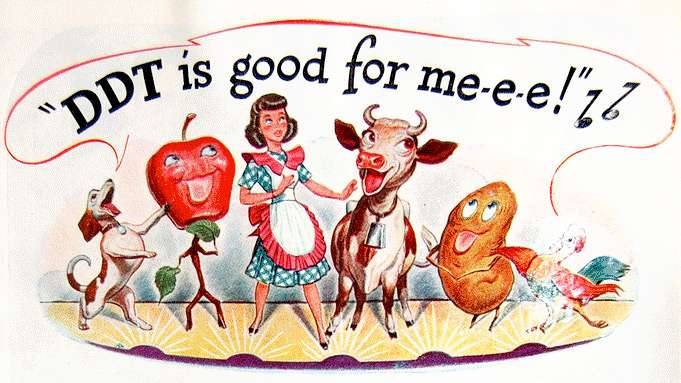

Featured above: An overly enthusiastic endorsement for dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane.

Show Notes

A Quick Favor To Ask: If you’re enjoying the show so far, I would really appreciate if you would nominate The Episodic Table Of Elements for a Podcast Award. For instructions on how to do just that, and read more about why that would be such a huge favor for the show, check out the earlier blog post on the subject.

You Know Something John Snow: I found a particularly good short documentary about John Snow and the Broad Street pump on YouTube, and recommend giving it a watch if you’re not familiar with the story! Plus, that video thumbnail is just great.

Author Steven Johnson hosted a PBS miniseries a few years back called How We Got To Now, along with a companion book and several companion articles that can be found on the web. It was an excellent little series, quite reminiscent of James Burke’s Connections miniseries that aired back in the 70s. (Itself an incredible series and something of an inspiration behind this podcast.) In one of those articles, he explains how element 17 led to one of the most revolutionary fashions of all time:

Consider the early 20th-century scientific and public health breakthrough of adding calcium hypochlorite (or chlorine) to drinking water to kill bacteria. This innovation had a dramatic impact on mortality rates, but it also transformed our recreational habits. After World War I, ten thousand chlorinated public baths and pools opened across America; learning how to swim became a rite of passage. These new aquatic public spaces were the leading edge in challenges to the old rules of public decency during the period between the wars. Before the rise of municipal pools, women bathers generally dressed as though they were bundled up for a sleigh ride. By the mid-1920s, women began exposing their legs below the knee; one-piece suits with lower necklines emerged a few years later. Open-backed suits, followed by two-piece outfits, followed quickly in the 1930s. “In total, a woman’s thighs, hip line, shoulders, stomach, back and breast line all become publicly exposed between 1920 and 1940,” the historian Jeff Wiltse writes in his social history of swimming, Contested Waters.

The whole article is well worth reading in full, and the series is definitely worth watching if it’s airing on your local PBS station!

A Hard-Learned Lesson: In the 1990s, Greenpeace led an extremely ill-advised campaign based on dubious research indicating that chlorinated water may cause cancer. They managed to convince some important people in Peru, who stopped chlorinating their water supplies.

Predictably, horrible outbreaks of cholera soon followed. No cases of cancer are thought to have been prevented.

No one really needed any further proof that chlorination saves lives, nor that Greenpeace probably causes more harm than good in the world. But just in case, there you go.

Apologies To Limerick Originalists: I admit that I have made a minor edit to the limerick mnemonic about DDT. Every other version of the limerick includes as its fourth line, “para-dichloro,” but no non-limerick source actually refers to DDT with the “para-” prefix. Thus, I took the liberty of altering the limerick. Pray I do not alter it any further.

Nothing Out Of The Ordinary Here: Just for illustration, one of those “mosquito fog” photographs I mentioned in the episode:

DDT Disbelievers: This entire essay on Dorothy Colson’s fight against DDT is an incredible, admirable piece of scholarship well worth reading in its entirety. It’s a true testament to the value of documenting local history in such painstaking detail, even if it might not seem worthwhile for decades.

Episode Script

We’ve spent the past couple episodes in a rather uncomfortable place: With phosphorus, we met Lucifer, then we spent some time in his neighborhood with sulfur. It’s time to leave all that behind, but to do so, we must follow in the footsteps of Dante Alighieri.

Dante was a 14th-century Italian poet whose most popular work was an epic narrative called The Divine Comedy. In it, the Roman philosopher Virgil leads the author himself on a tour through the Christian afterlife, starting in Hell, and ending in Heaven. But in order to get from one to the other, he must first travel through Purgatory: The state of being for souls whose sins didn’t condemn them to Hell, but need to be cleansed, or purged, before entering Heaven. This cleansing is often imagined as happening by fire.

In part, this was established by Pope Gregory the Great, who claimed that the purifying fire of Purgatory could only wash away minor sins, and not “iron, bronze, or lead.”1

Chlorine is quite similar. As a powerful oxidizer, it can light just about anything on fire — even iron and bronze, although not lead2 — and we do use element 17 as a cleaning agent to purify our water and keep our clothes bright white.

So, if I may act as your auditory Virgil, let us proceed through Chemical Purgatory.

You’re listening to The Episodic Table Of Elements, and I’m T. R. Appleton. Each episode, we take a look at the fascinating true stories behind one element on the periodic table.

Today, we’re keeping it clean with chlorine.

Most of the time, we’re not very well acquainted with an element before it gets its own episode, but we’ve bumped into chlorine several times already on the show. In fact, we’ve probably already told all of its most famous stories: Its use as a chemical weapon in World War I, which we discussed in Episode 7; its presence in sodium chloride, AKA table salt, in Episode 11; and even as an integral part of the ozone-eating chlorofluorocarbons, featured in the blog’s most recent Element Update.

But chlorine is a remarkable atom, with many more stories to tell. And much like Fritz Haber, the warrior chemist who also happened to feed the world, chlorine eludes a verdict as simply good or bad.

As we’ve learned, you really don’t want element 17 to find its way up your nose, but you should be very thankful that you can find it in your mouth.

Only a century ago, it was more likely than not that a person’s drinking water was festering with fecal bacteria. If that makes you feel sick to your stomach, just imagine what that did to the people who actually had to drink it.

Or, don’t imagine, because I’m about to tell you: It killed people, by the hundreds and sometimes thousands, through outbreaks of cholera, typhoid, dysentery, and a host of other diseases spread by filthy water.

This slowly started to change in the latter half of the 19th century. Thanks to landmark work done by scientists like John Snow, Jonas Salk, and Louis Pasteur, people began to understand what caused these diseases, how they spread, and how they could be prevented.

Each of those men performed legendary works of research and discovery, and that means their stories have been told many times, by many people, in many places. So, all respect to Misters Snow, Salk, and Pasteur, but today I’d like to focus on a lesser-known hero of public health.

John Leal was born in upstate New York, the year 1858. His father was a physician, and while fighting in the Civil War, he came down with a case of amoebic dysentery brought on by foul water. This disease would eventually kill John’s father, but not before making him suffer through 17 years of illness.

It seems obvious, then, why Leal would be particularly concerned about clean drinking water.

He was educated at Princeton and Columbia Universities, then opened a private medical practice and joined his city’s Board of Health. By 1908, Leal was living in New Jersey and working as an adviser to local water supply companies. There was plenty of work to do. Jersey City had been dealing with contaminated water for decades, and tens of thousands of people had died from typhoid and similar diseases. Leal was part of the team tasked with cleaning up that water supply.

Everyone knew that water could be purified by boiling it, but it wasn’t possible to boil the city’s entire water supply. They thought about installing new sewage and drainage systems, but that was looking prohibitively expensive — and Leal suspected that wouldn’t actually solve the problem, anyway. Instead, he was thinking about some scientific trials that had recently taken place in Europe.

Doctors had only recently discovered the existence of germs and their connection to illness. When outbreaks of waterborne illness struck cities in England and Germany in the late 1800s, officials tried adding chlorine to the water, and that killed off the nasty diseases. But those were emergency measures — no one had attempted or even tested the effects of long-term water chlorination.

At the time, scientists saw chemicals like chlorine as poison, something only a madman would ask people to drink. Make no mistake, chlorine is toxic, but remember what Paracelsus taught us about poisons: It’s the dose that makes ’em.

That’s what Leal was concerned with. He had run plenty of tests, and believed that at a low concentration, chlorine could effectively kill microscopic life while remaining safe for larger animals. He also knew that no one — politician, scientist, or civilian — would let him chemically treat the drinking water.3

So he didn’t ask for anyone’s permission.

Leal hired an engineer named George Warren Fuller, and in complete secrecy, the two spent ninety-two days designing and building a device that fed calcium hypochlorite into the Boonton Reservoir. It worked flawlessly, and not a soul found out.

Well, not until three days later, when Leal had to explain to a judge exactly how he had completed his assigned task. He did not play coy about what he’d done, and the judge was gobsmacked.

Do you drink this water yourself?” he asked, incredulously.

“Yes,” said Leal.

“Habitually?”

“Yes.”

“And you would not hesitate to have your family drink this water?”

“I believe this is the safest water in the world today.”

What was intended to be one afternoon’s routine legal proceeding stretched on for 38 days, with citizens protesting outside the courthouse. They called Leal a maniac and a criminal, which is honestly pretty understandable. Secretly dumping toxic chemicals in the municipal water supply is usually what the Scarecrow tries to do when Batman’s not looking.

At one point, the judge realized that what they were dealing with was unprecedented in scale.

Q: Doctor, what other places in the world can you mention in which this experiment has been tried of putting this bleaching powder in the same way in the drinking water of a city of 200,000 inhabitants?

A: 200,000 inhabitants? There is no such place in the world. It has never been tried.

Q: It never has been.

A: Not under such conditions or under such circumstances but it will be used many times in the future, however.”4

That may sound audacious, but Leal knew the results would speak for themselves. Deaths by typhoid fever in Jersey City had immediately fallen by half, and would fall by half again within two years. By 1940, almost every community in the United States was drinking chlorinated water, and almost nobody was dying of waterborne diseases.5

The rapid, extensive deployment of this lifesaving technology was only possible because Leal sought not to profit from his innovation. Even at the time, many found this difficult to believe. While he was still on the stand, the prosecuting attorney said as much. “And if the experiment turned out well,” he accused, “why, you made a fortune.”6

Leal corrected him, “I don’t know where the fortune comes in. It is all the same to me.” He had never even considered patenting his chlorination process. Leal was simply a man who wanted no one else to see a family member suffer and die from tainted water ever again.

The lawsuit shook out in Leal’s favor. When the case was closed, the report read, “This device is capable of rendering the water delivered to Jersey City, pure and wholesome.” And that was the last time anyone complimented the drinking water in New Jersey.

The chronicle of chlorination is an actual case of Better Living Through Chemistry.

Incidentally, that’s a phrase with some interesting history of its own.

DuPont has been a goliath of the chemical industry since World War I, and that timing is no coincidence. After all, someone had to manufacture all those bombs, bullets, and bottles of poison gas, and by 1920, the DuPont family’s gross income exceeded one billion dollars.

This sort of profiteering quickly earned DuPont and similar corporations a reputation as “merchants of death.” To say their public image had been tarnished would be an understatement.

DuPont sought to rehabilitate their reputation with propaganda presented as educational entertainment. The Cavalcade Of America was their weekly biography show on the radio, and later television, that aimed to foster good will toward the company. It did so by celebrating the American values of ingenuity, resilience, and gumption, exemplified by scientists and artists both famous and unknown throughout history. Occasionally it would squeeze in a word about the evils of labor unions and antitrust lawsuits, too.7

This all helped create a new public image of DuPont, not as a munitions corporation that had tried to prolong global war for personal profit, but as a philanthropic patron of the arts that happened to employ America’s brightest minds. And it did so while repeating a catchy motto:

DuPont used the slogan, “Better things, for better living, through chemistry,” for decades, and it was so well-known that it inspired a legion of imitators. “Better Living Through Chemistry” was apparently just vague enough to skirt trademark law, and subsequently made its way into the culture’s collective unconscious. “Better Living Through Chemistry” has been used as a title for books, songs, and at least one terrible romantic comedy about a pharmacist.

Although the phrase has picked up some negative connotations since it first hit the airwaves, it resonated with people for a reason. Chemists had undoubtedly raised the standard of living in industrialized countries. And the miracle of clean drinking water was still pretty fresh in everyone’s mind when chemists tried their hand at eliminating another deadly disease vector: Insects.

For most of human history, pesticides have been kind of a blunt-force object: Poison. The kind of poisons that experts call “broad-spectrum.” That is, they’ll kill just about anything: Rats, cockroaches, locusts, mosquitoes… and humans.

But in the early 1930s, a researcher named Paul Herman Müller discovered that insects interact with certain molecules in ways that other life does not, which led him to believe there could be a safer insecticide. One that could be employed without fear of killing people.

Three hundred forty-nine times, he tried and failed to find such a chemical, but on the three hundred fiftieth, Müller found just the thing: A chemical that was cheap, long-lasting, and effective against a wide range of invertebrates, while avoiding the danger to humans presented by earlier arsenic-based pesticides.8

That chemical’s name is kind of a mouthful, but some helpful anonymous soul has provided a clever mnemonic that makes it easy to memorize:

A mosquito was heard to complain,

“A chemist has poisoned my brain!”

The cause of his sorrow

A dose of dichloro-

Diphenyltrichloroethane.

Or, if you insist, I suppose you could call it by its abbreviated name: DDT. Those two “chloro”s in the name indicate that element 17 is an integral part of this molecule.

DDT was a revolutionary pesticide. Its original use as a de-lousing powder among soldiers practically eliminated typhus, a deadly disease that had followed in the wake of every prior war. When put in the hands of civilians, widespread use of DDT eradicated malaria from Europe and North America entirely. It’s difficult to overstate what a powerful tool of public health this was. Despite not being a medical doctor, and never conducting any medical research, the Nobel Prize committee awarded Müller the 1948 Nobel Prize in Medicine.

Of course, mosquitoes are everywhere, so eliminating malaria was no small task. DDT was sprayed with abandon on crops, houses, and people’s skin. It’s easy to find eerie photos of children playing in the “mosquito fog” sprayed by trucks blanketing entire suburbs with insecticide.

Sometimes, the people of this era get painted as naive, often to the point of absurdity. Select cultural artifacts make this easy to believe. For instance, a full-page ad in TIME Magazine from 1947 features a chorus of plants and animals joining a farmer to sing, “DDT is good for me-e-e,” with copy that promises “20% more milk” and “50 pounds more beef,” in a “healthier, more comfortable home.” All because the bugs have been kept at bay with DDT.

But this is not some joyous exultation from the people of postwar America. This is commercialism. In particular, this is Penn Salt Chemicals exhorting you to buy their brand of DDT, and oh, by the way… “DDT is only one of Pennsalt’s many chemical products which benefit farm, industry, and home.”

People who were not corporations did not always share that enthusiasm.

Early critics were people who actually had to deal with the stuff. Dorothy Colson was a woman living in Claxton, Georgia, a farming community. As early as 1945, she suspected that all those billowing chemical clouds diffused across the land by airplane might have something to do with all her dead baby chicks. And her dairy cows who had become mysteriously sick. And her own daughter’s incurable sore throat.9

No one thought the stuff came without risks. It was front-page news in the Washington Post when the Army announced it would sell surplus amounts of its phenomenal delousing chemical to civilians, and the first sentence of that front-page story cautioned not to use DDT “to upset the balance of nature.”

Civilians may well have heeded that warning, but they wouldn’t be the ones wielding that kind of power.

DDT also increased crop yields like nothing that had come before it, except maybe synthetic fertilizer. Newly created chemicals like vitamins, antibiotics, and vaccines were helping the same thing happen with livestock, too. Combined with cheap fuel and mechanical tools, the stage was set for a new kind of farming: Industrial agriculture, dominated not by individuals, but companies with vast reserves of wealth.

Local farmers frequently found themselves, very literally, left in the dust of their corporate neighbors. Farmers like Dorothy Colson found themselves turned into activists, sometimes fighting simply to know what kind of chemicals they were being forced to choke down as they struggled to get by, since nobody bothered to tell them. She once wrote to then-Governor Herman Talmadge, “Can we hope to enjoy good health in Georgia and have this happiest opportunity? Or must we be poisoned to death in our own homes?”10

She and others like her were dismissed. Those in power paid more attention to dollars and cents than the concerns of housewives. That is how Colson and her peers, mostly women, were seen: They were “overanxious,” the danger was “all in their minds,” they were “hysterical.”

So DDT became an accepted part of life. But it wasn’t long before another woman began pulling at the threads.

In 1957, the US Government was trying to eradicate the gypsy moth, an invasive species that causes terrible damage to trees. Every six-legged problem looked like a nail, so the Department of Agriculture whipped out that good old hammer of pesticides, DDT.

The people of Nassau County, New York, were displeased. A particularly nasty mixture of DDT and fuel oil and an indiscriminate application method had caused quite a scene: A woman got drenched in the stuff. Children and commuters were similarly doused, and a horse was killed.11

The legal fallout caught the attention of a reporter named Rachel Carson. After some preliminary research, she told her editor that she thought there was enough material to make for a pretty long article.

She began pulling all sorts of information together from many disparate sources, and it started to become clear that DDT was having some unintended side effects. For one thing, it didn’t just kill the “bad” bugs, like mosquitoes and locusts. A lot of insects are critically important to plant life as pollinators, and even those that aren’t are still an essential part of an ecosystem’s food web. DDT made no distinction.

Speaking of food webs: Insects comprise a meaningful portion of the diet of birds. So first the birds would get coated alongside the insects in the initial spraying, then if they did manage to find any surviving bugs, the birds would get an internal dose with every meal. Fish were likewise affected.

DDT is also a molecule that tends to bioaccumulate; that is, biological bodies have a difficult time getting rid of it once it’s found its way in. We’ll see this with other chemicals too, especially heavy metals like lead.

This slowly growing dose of insecticide wasn’t particularly harmful for adult birds, but it did cause their eggs to have abnormally soft shells. Chicks couldn’t hatch properly, if they were even viable at all. Bird populations plummeted. The bald eagle, national bird of the United States, wound up on the endangered species list primarily because of DDT.

And the renowned effectiveness of the chemical seemed to be fading, too, due to a phenomenon similar to antibiotic resistance. DDT would kill off the vast majority of an insect population… but those that survived would reproduce, and pass on that resilience to the next generation. We were unintentionally breeding insects that could survive our chemical attacks.12

These were the kinds of things that Rachel Carson was discovering. She wasn’t the first person to learn about the havoc DDT could wreak, but she was the first person to collect these stories and present them in a way that made people pay attention. They started as a series of articles in the New Yorker, but Carson had an entire book’s worth of material.

In 1962, that book was published. It was called Silent Spring.

Immediately popular with the reading public, today the book is considered a touchstone and foundational text of the environmental movement.

In Silent Spring, Carson called for no extreme measures. Her message was one of prudence: Perhaps, she suggested, we should try to gain a more complete understanding of any particular chemical before plastering it on every visible surface.

The major chemical companies, of course, were not pleased. They started pumping out brochures, newspaper articles, and films in retaliation, but the Misinformation Playbook was not yet as refined as it would be by the time the tobacco and petroleum industries put it to use. Their floundering only served to make more people curious, and kept Silent Spring number 1 on the bestseller list for 39 weeks13

Public pressure led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, and a near-total ban on the use of DDT in the United States in 1972. Many other countries followed suit over the next several years.

There is no doubt that this was a victory for biodiversity. The bald eagle population rebounded over the next several decades and is once again thriving. Other birds, freshwater fish, and pollinating insects were also able to recover.14

Even so, an outright ban might have been an overcorrection. After all, DDT was one of our most powerful weapons in the fight against malaria, a disease that still kills hundreds of thousands people every year.15 And there are safer ways of applying DDT. Applying it carefully to home interiors can be just about as effective as the crop-dusting method, and causes far less of the chemical to leach into the surrounding environment.

But even if DDT came back in full force around the globe to combat blood-borne diseases, it’s not clear that it would work anymore. Insects breed quickly, and are able to develop chemical resistances in a surprisingly short time span. In 1956, five species of mosquito displayed resistance to DDT. Within four years, an additional 23 species were also able to survive the pesticide.16

As the world grows warmer, tropical insects are able to flourish and spread into territories that were previously too cold. Diseases like West Nile, Zika, and Vibrio present a growing threat, and malaria could very well reestablish itself in North America.17 Societies around the world will need to decide how to protect themselves.

Knowing all this, we should not conclude, “Environmental concerns lead to overreactions,” nor should we assume that, “Synthetic chemicals will be our doom.” We merely need to learn how to act in a considerate and deliberate manner with the powerful tools we continue to discover.

The discerning collector should also act in a considerate and deliberate manner when pursuing chlorine, lest they render their entire neighborhood uninhabitable with a cloud of poison gas. It is relatively simple (and wildly dangerous and highly inadvisable) to isolate element 17 by mixing sodium hypochlorite and any acid to make chlorine gas. Storing the gas is a much more difficult matter, and is left as an exercise for the listener.

Whether a purist or not, the element collector can likely secure today’s prize without leaving the house.

The most obvious place to start will be the laundry room, where many people keep a bottle of chlorine bleach. As a strong oxidizing agent, bleach kind of works like a chemical sponge, sopping up electrons from stains, allowing them to be rinsed away and leaving bright white clothes and linens behind.

Moving on to the pantry, chlorine is the jelly to sodium’s peanut butter in that molecule we know and love as salt. Turns out sodium chloride is delicious for a reason: We’ve already learned how our bodies snap off the sodium atoms for use in the nervous system, but the chlorine is used to produce gastric acid. If we didn’t eat salt, we wouldn’t be able to eat anything else!

Let’s proceed to the bathroom. If you were paying attention earlier, you know that chlorine is one of those elements that gets piped directly into our homes, via tap water. What’s not so obvious is that often, chlorine is part of the pipes themselves.

That’s what the C stands for in PVC: Polyvinyl Chloride. It makes for an extremely versatile plastic that’s ubiquitous in modern life, not only for pipes, but for plastic bottles, packaging, credit cards, and much, much more.

It’s a little surprising that such a volatile element is so often within arm’s reach, but that’s a modern luxury. Most of these chlorine compounds didn’t even exist a few hundred years ago. Back then, the most effective way to bleach cloth was by leaving it out in the sun. Water was full of bacteria, and usually ferried through lead pipes, if there was any plumbing at all.

I must admit: We’ve found much better things, for better living, through chemistry.

Thanks for listening to The Episodic Table of Elements. Music is by Kai Engel. To learn how chlorine led to a fashion revolution and find out what happens if you stop chlorinating the water supply, visit episodic table dot com slash Cl.

Next time, we’ll kick back with Argon.

This is T. R. Appleton, reminding you that you have until July 31, 2018 to nominate The Episodic Table Of Elements for a podcast award. To learn how and why you could do such a thing, I would really appreciate if you’d visit episodic table dot com slash award.

Sources

- Chapter XXXVII of this work by that pope says as much, if you care to translate it. Do a “Find in page” for “plumbum.”

- Periodic Table of Videos, Chlorine. 7:27.

- SafeDrinkingWater.com, John L. Leal — Hero Of Public Health. Michael J. McGuire, September 25, 2012. Ordinarily I wouldn’t source from a website like this, but it happens to be written by the same man who wrote The Chlorine Revolution, a widely respected book on the subject.

- In Chancery of New Jersey, Between The Mayor And Aldermen Of Jersey City, Complainant, And The Jersey City Water Supply Company Et. Als, Defendants. p. 4,978.

- Water Quality & Health Council, Chlorination Of U.S. Drinking Water. May 1, 2008.

- Steven Johnson, How We Got To Now: Six Innovations That Made The Modern World. No page number given.

- The Citizen Machine: Governing By Television In 1950s America, p. 38-44. Anna McCarthy, 2013.

- Prometheans In The Lab: Chemistry And The Making Of The Modern World, p. 153. Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, 2001.

- Science History Institute, Beyond Silent Spring: An Alternate History Of DDT. Elena Conis, Winter 2017.

- Southern Spaces, DDT Disbelievers: Health And The New Economic Poisons In Georgia After World War II. Elena Conis, October 28, 2016.

- The New Yorker, Silent Spring — II. Rachel Carson, June 23, 1962.

- The New York Times, Rachel Carson, DDT And The Fight Against Malaria. Clyde Haberman, January 22, 2017.

- The New York Times, Rachel Carson Dies Of Cancer; ‘Silent Spring’ Author Was 56. Jonathan Norton Leonard, April 15, 1964.

- US Fish & Wildlife Service, Bald Eagle Fact Sheet.

- UNICEF, Malaria Fact Sheet.

- Journal Of Military And Veterans’ Health, DDT And Silent Spring: Fifty Years After. Cristobal S. Berry-Caban, Issue Volume 19 No. 4.

- National Geographic, Climate Change Pushing Tropical Diseases Toward Arctic. Craig Welch, June 14, 2017.

A lot of interesting information and facts, but I am sorry but I think you are rambling too much. A lot of good nuggets, but too much side tangentials about people and their melodrama, too little specific information about the actual elements themselves. No offence, just my honest opinion, I overall love your website anyways, cheers!

personally that’s what i love about this podcast. other people have talked at great length about chemistry elsewhere but this for me is the perfect intersection of chemistry, and how it goes on to affect the world. i can come away with memorable stories so that when someone mentions chlorine, i can remember the story of the court case and how it got in our water supply, and the story of DDT, and it’s precisely the specific detail that makes it all memorable. it’s a matter of opinion of course, but if you want specific info on the chemistry of chlorine i’m sure there are lots of explainers on youtube. meanwhile, i love what you’re doing with this show t r appleton, thank you for maintaining my interest in chemistry through your excellent explanation style!