Podcast: Play in new window | Download

All other metals step aside, because today we deal with the king of elements.

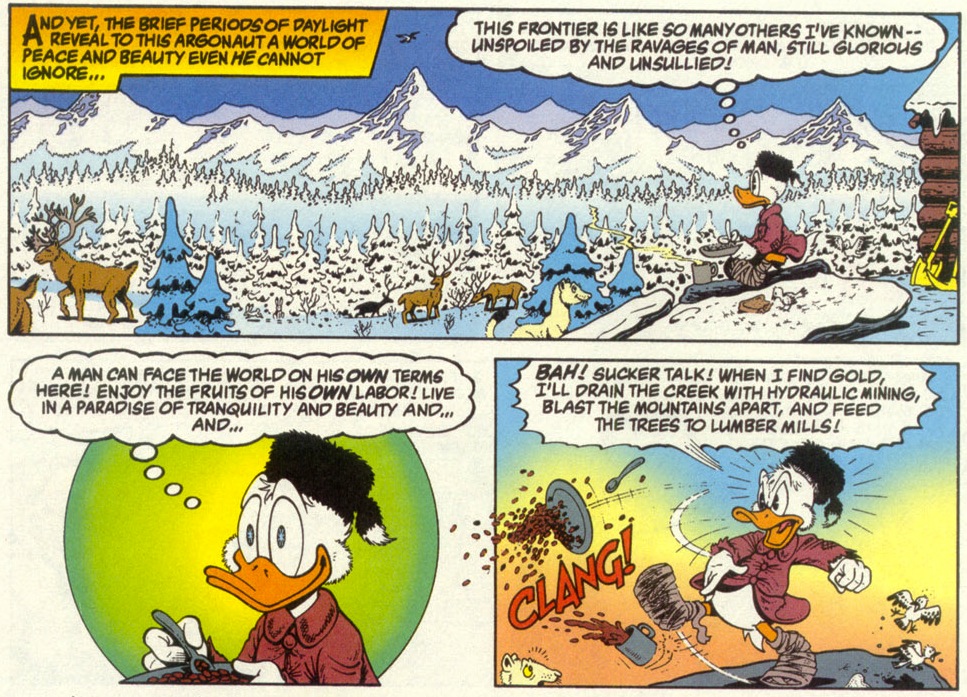

Featured above: This comic is fiction, but what my theory presupposes is, maybe it’s not?

Show Notes

Holy moly! I got this one out the door later than I would have liked. Show notes will be forthcoming, same with sources. In the meantime, enjoy these videos of harsh chemicals going on a rampage, and if you were curious, the answer is, “A cube twenty meters per side.”

As of April 12, 2021, I’m finally getting around to adding the references in. Oy! Not even close to finished yet though. My apologies.

Episode Script

Gold: surely the most coveted of all the elements, even by those who couldn’t care less about chemistry. It’s also one of the few elements that humanity has known since our earliest days on Earth. These two factors have helped element 79 attain an honored position across all times and cultures, even providing narrative fuel for some of history’s most famous myths: The goose that laid the golden egg, El Dorado, Jason and the Argonauts, Cáishén (Tsai Shen, 財神) and his golden cudgel, the seed of Agni, Auric Goldfinger, and Scrooge McDuck — to name but a few.

Of all the many characters with a penchant for gilded goods, the most notorious might be King Midas. You’re probably already familiar with the fable of the Phrygian king. When granted one wish by the god Dionysus, he foolishly asked for his touch to turn ordinary materials into gold. He delighted in aurifying his rose garden, tableware, and furniture, but his newfound ability worked too well. Food and drink also turned to gold, beautiful but inedible, and when he reached out to comfort his daughter, so too was she petrified in golden splendor.

It’s a tale that goes back at least as far as Aristotle, but less well known is the fact that King Midas was a real historical figure — or perhaps a few members of one family — who ruled an area of modern-day Turkey around the 8th century BCE. In 1957, a group of archaeologists discovered the tomb of one of these men. It was an extravagant chamber, full of shiny cauldrons, gleaming bowls, and a skeleton adorned with a lustrous metallic belt.

Analysis of these artifacts revealed them to be not gold, but an alloy of copper and zinc: brass. Brass is similar to bronze, but with a sheen that can almost be mistaken for gold. Coincidentally, back when Midas was king, Phrygia was one of the few places in the world with the technology and the raw materials necessary to manufacture brass. Visitors to his kingdom probably knew that the glittering adornments weren’t genuine gold, but they were still beautiful and rare. Add a few centuries of travelers telling tales, and it’s easy to see how brass could be transformed into something more precious.

Of course, there’s nothing quite like the real thing. In gold we have an element unlike any other, one that has played a critical role in the history of chemistry, medicine, economics, religion, and war, from antiquity to modern times. So strap in, because when it comes to tales about gold, we have an embarrassment of riches.

You’re listening to The Episodic Table Of Elements, and I’m T. R. Appleton. Each episode, we take a look at the fascinating true stories behind one element on the periodic table.

Today, we’re panning for gold.

Call me biased, but it seems clear to me that the reason element 79 has played such a prominent role throughout history is because of its electrons. Gold is one of the so-called “noble metals,” elements which, like the noble gases, hold on to their electrons tightly, and thus barely react with other chemicals.

That’s a little counterintuitive, though. Gold is in the middle of the periodic table, far from the reactive alkali metals of group 1, and even farther from the completely inert noble gases in group 18. Based on its location, you might guess that gold would be about as reactive as iron — not something explosive (usually), but an element that readily forms oxides. Yet it does not.

It becomes even more confusing when you look at gold’s electron configuration. Its valence shell is occupied by only one electron, something it has in common with hydrogen, caesium, and the other elements in Group 1. Based on that knowledge, you might think that gold should fizz, or maybe even explode, when it comes in contact with water. Yet it does not.

Strange things start to happen as elements become more massive, and sometimes these things give rise to complex behavior that defies the simple trends that define the lighter elements. In this case, gold’s one valence electron orbits the nucleus very closely, and also very quickly — faster than half the speed of light. In practice, that makes this one valence electron really difficult for other atoms to access. The other orbitals, which are all full, essentially shield the valence electron from chemical reactions.

This allows gold to be found in its pure, elemental state, and it can maintain its beautiful luster for thousands of years. Gold can even stave off attacks from some of the harshest chemicals, like bleach and sulfuric acid. Even sodium hydroxide has no effect, and that stuff can chew through glass like it’s nothing.

However, gold is not completely impervious from chemical attack. It is possible to brute-force a reaction using some very, very strong acids. Neither hydrochloric acid nor nitric acid alone can do much to it, but a three-to-one combination of them will make gold dissolve in solution. The nitric acid oxidizes some of the gold, and the resulting gold ions interact with HCl to form chloroauric acid. Basically, nitric acid sets ’em up, and hydrochloric acid knocks ’em down. The nitric acid is then freed up to oxidize more gold, which then combines with chlorine, and so on.

This mixture of acids is called “aqua regia,” and on one occasion, its power was exploited to execute some very clever subterfuge.

The Nazis loved gold. They were using it to fund the war, and they took it from anyone who had it — enemies whose territory they had invaded, as well as their own citizens — especially those who were Jewish.

Max von Laue was a vocal critic of the Nazi party, and James Franck was Jewish.2 To prevent the Nazis from confiscating their medals, they sent them to friend and colleague Niels Bohr, who lived in Copenhagen, Denmark — free from fascist rule.

At least, for a while. On April 9, 1940, the Nazi army invaded Denmark and seized power with little opposition. Niels Bohr and George de Hevesy were in their lab, struggling to decide what to do with these two very conspicuous lumps of gold. They decided not to bury them like treasure, because the Nazis would probably dig up the entire yard to find them.

de Hevesy had a better idea, and you can probably guess what it is. He completely dissolved both medals in a solution of aqua regia while the Nazis marched down the streets of Copenhagen. He poured the solution into a beaker and set it on a shelf. Even though stormtroopers searched high and low, none of them suspected that an innocuous container of liquid contained several mols of element 79.

de Hevesy returned to the lab five years later, and found the beaker entirely untouched. He extracted the gold back out of the solution and sent it to the Swedish Academy, where the raw material was used to cast new medals that were presented to Franck and von Laue in 1952.

The people most closely associated with aqua regia were not chemists, but their historical predecessors, the alchemists. Being one of the few substances capable of having any effect on gold, they made extensive use of aqua regia in their attempts to transmute other metals into gold. If you remember all the way back to episode 11, you might recall Basil Valentine’s cryptic instructions to prepare “a mineral bath for the king.” That was a direct allusion to aqua regia.

Turns out it is possible to transform other metals into gold, but no one succeeded in that task until 1924. That was when Hantaro Nagaoka, a professor at Tokyo Imperial University, knocked the proton loose from some mercury atoms, turning them into gold. In 1972, Soviet scientists at a nuclear power plant converted lead to gold entirely accidentally! What had eluded the world’s brightest minds for centuries became entirely possible in the twentieth century, but only with the aid of cutting-edge instruments of atomic physics — not aqua regia.

The alchemists’ quest for gold was closely intertwined with the pursuit of immortality and a cure for all diseases. In fact, gold might be humanity’s first medicine, having been prescribed by healers and shamans at least as far back as 2500 BCE. It’s been used to treat just about every possible illness, from heart murmurs to impotence.3

Unfortunately, gold doesn’t actually do anything to cure those maladies, but there are some legitimate medical uses for gold. Most obvious of these is its use as a dental implant — that is, a gold tooth. Being so incredibly resilient, it’s one of the few materials that can withstand decades of chemical attack in the hostile environment that is the mouth.

Element 79 has occasionally been used as a prosthesis elsewhere in the body, too, perhaps most outrageously in the case of Tycho Brahe. The 16th-century Dane was as brilliant as he was eccentric. He first postulated the existence of stellar novae, and he also employed a supposedly psychic dwarf jester who stayed under the dining room table during parties. He discovered the atmospheric refraction of light,4 and he also kept an alcoholic elk in his castle. (One night the elk had too much to drink, fell down the stairs, and died.)5 6 7 8 9 10

Brahe was also a man of strong passions. When he was around 20 years old, he got in a fight with his cousin at one of the many social affairs he attended. The subject of this fight is unknown. It could have been a matter of chivalrous honor, but it’s equally likely to have been about mathematical formulae. Whatever the perceived offense, it ultimately resulted in the two young men drawing swords for a duel, and Brahe lose a sizable chunk of his nose in the process. He obfuscated this mutilation with a false nose that he wore for the rest of his life, and might have even owned several different noses for different occasions. Brass, copper, and yes, gold have all been suspected as the material adorning the hard-partying astronomer’s face. Presumably, this only added to his mystique.

Modern medicine has found verifiably effective uses for gold as a pharmaceutical. It’s now used to diagnose and treat a surprisingly diverse array of illnesses, from malaria to HIV to cancers of any kind.

But the lifesaving powers of gold, real or imagined, are not the element’s main appeal. French physician Étienne François Geoffroy (jo-foi) explained rather wryly:

“ze mahst vahluable ahnd mahst precious of ahll metahls,” he once said, “ees ze mahst useless een physeeck, except when cahnsidered ahs ahn ahnteedahte to pahverty.”

“The most valuable and most precious of all metals,” he once said, “is the most useless in Physick, except when considered as an antidote to Poverty.”11

Indeed. Gold is one of the few metals that naturally occurs in its elemental form, no processing required. It’s also just rare enough: scarce, but common enough to be found almost anywhere in the world. Combined with its nigh-eternal endurance and unparalleled warm color, it’s easy to see why cultures around the world have historically chosen gold as a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a way to flaunt one’s wealth.

For most of human history, as far back as 100,000 years ago, goods were usually just given from one person to another, sometimes with the expectation of a gift in return, sometimes not. People did occasionally barter — “I’ll give you my five chickens for your fox pelt,” or whatever — but usually only if the two parties didn’t know each other or didn’t like each other.12 13

These systems have some inherent inconveniences, though. Maybe I don’t need your five chickens right now, or perhaps you don’t want to be in my debt. That’s where something like gold comes in handy. You can give me a shiny gold coin in exchange for my fox pelt and our transaction is complete. I can then hold on to that coin as long as I need and later exchange it for something someone else has.

The earliest known coins started appearing between 2,500 and 3,000 years ago, in the areas now known as Bulgaria, Turkey, Egypt, and China, places that acted as crossroads for several different cultures.14 Usually those coins were made of gold, or its elemental siblings, copper and silver, which share many of gold’s chemical properties. This comes with its own set of problems, of course, especially counterfeiting, a tradition so time-honored that it’s sometimes called “the second-oldest profession.” Then again, people make that claim about a lot of jobs, from acting to espionage to medicine. At least we can all agree what our first priority was.15

Whenever the first person passed off a fake coin, merchants quickly found countermeasures to employ in response, and said countermeasures left a remaining influence in our language. Gold is a very soft metal, so scratching it against a dark, textured surface like slate will leave behind a telltale mark. It’s not a binary thing, either. Gold mixed with less valuable metals will leave behind a fainter mark on the slate’s surface.16 This innovation became known as a touchstone.

In 1773, silversmiths in Sheffield, England opened an assay office where independent experts would judge the quality of precious metals and leave an insignia imprinted upon it. A mark made in the guildhall — this is the origin of the term “hallmark.”17

Gold has been the lifeblood of empires. Patriotism is great, but nothing motivates a soldier quite like cold, hard cash. It’s right there in the name, actually: “Soldier” comes from the Latin “soldarius,” which literally means “a person who gets paid.” And while there were many sundry reasons that Rome fell ins prestige around the 5th century CE, there’s evidence that one of those reasons may have been a lack of gold.18

Rome had been trading with its Eastern neighbors for centuries, especially India and China. The Romans bought silk, ivory, incense, spices, and more, but there weren’t really any European goods that interested Asian merchants in return. Gold was literally the only valid currency the Romans had. And while the empire’s coins steadily trickled eastward, the coffers never really filled back up. Rome’s production of silver and gold peaked around the 1st century CE, and fell sharply afterwards. Unable to maintain an elite military, Rome’s armed forces started to resemble ragtag mercenaries, or a particularly ineffective border patrol.19

But even at the height of its glory, the wealth of Rome was nothing compared to that of the Mali empire about a thousand years later. That was during the reign of Mansa Musa I, who is a serious contender for the title of “Richest Person Who Ever Existed.”

At the time, Mali was the largest empire in West Africa, stretching more than 2,000 kilometers wide. Musa came to power in 1312. (Mansa was a title, roughly analogous to “Caesar” or “Conqueror.”) He was a devout Muslim, and as such, it was his duty to perform the Hajj. Every adult Muslim is obligated to make a pilgrimage at least once in their life to the city of Mecca, birthplace of the Prophet Mohammed and the holiest city in Islam.

This can be an arduous journey to make nowadays, even with the benefit of air travel, but Musa had to travel more than 4,000 kilometers from Mali’s capital city of Niani on foot. Well, actually, he got to ride a horse. But pretty much everyone else he was traveling with had to walk, including the 500 slaves that preceded him, each of whom carried a staff decorated with gold.

And that was only a small portion of the total 12,000 slaves who came along for the trip, each garbed in fine Persian silks and carrying nearly two kilograms of gold bars and ornaments. In turn, the slaves only accounted for one-fifth the total entourage of 60,000 men. He was also followed by 80 camels, which might sound less impressive until you consider that each of those carried more than 100 kilograms of gold dust. Records are unclear whether he was actually accompanied by forty fakirs, and cooks and bakers, and birds that warble on key.

It wasn’t all just for show, either. Don’t get me wrong, it was very showy, but Mansa Musa was an incredibly generous sort. From Cairo to Medina to Mecca, he and his cavalcade gave out gold like beads at Mardis Gras. They flooded the market with so much gold, in fact, that runaway inflation became a serious problem, and parts of the Middle East were plunged into a deep, decade-long recession. Even twelve years later, Cairo had not yet fully recovered. Nonetheless, even many years afterward, those who had been the lucky recipients of Musa’s generosity had only good things to say about him.

It’s possible that this destabilizing effect was intentional on Musa’s part. Cairo was the one of the world’s leading gold markets back then, and tanking the economy could certainly make Mali look like a more attractive venue to hawk one’s wares. At the very least, Mansa Musa’s journey to Mecca was very successful in getting the word out about the glory of the Empire of Mali. After all, we’re still talking about it seven hundred years later.

As much as I wish it were true, I cannot promise that an incalculably prosperous emperor will deign to traipse through your hometown and distribute so many samples of element 79 that it causes a financial crisis. In fact, I’d go so far as to say it’s objectively less likely to happen today than it was in the 14th century. The good news is, gold might be the single most sought-after element in history, so there are many tried and true strategies you can use to add it to your own collection.

Mining for anything is backbreaking labor, and gold is no exception. But you don’t need to pull gold from the Earth, because there are places where the Earth will bring gold to you. These locations are called “placer deposits,” where gold naturally accumulates and is carried by the waters of a river. Panning is one way to extract the gold from such a site, and it’s practically free! Just scoop up some alluvial sand, swirl and sift for a bit, and with a little skill and a lot of luck, you’ll find yourself with a few bright flakes of gold.

If you’re really lucky, it’s not impossible to stumble upon nuggets of gold just lying on the ground. Aussies John Deason and Richard Oates are probably the luckiest people in history when it comes to that sort of thing. In 1869, they were trudging through the Victorian outback toward Bulldog Gully when they nearly tripped over the largest gold nugget ever found. Barely covered by a mere dusting of dirt near the base of a tree, the nugget was more than 60 centimeters long by 30 centimeters wide, and weighed nearly 100 kilograms. It became known as the “Welcome Stranger,” and the two men were paid more than 9,000 pounds for their find. That would be nearly three and a half million American dollars today.20 21

Historically, a find like that would set of a frenzy of prospecting — a gold rush. The nineteenth century was especially rife with gold rushes, from South Africa to Chile to Sibera, plus the ones you might already know about in California and the Yukon. They aren’t just relics of the past, either; there are gold rushes happening right now in Ghana, Siberia, and Texas.22 23

Don’t pack your bags just yet, though, because rarely do hopeful prospectors wind up acquiring the riches they’ve dreamed about. More often those brave souls were destined for heartbreak and poverty.

I wouldn’t be so glib as to say that’s a blessing in disguise, but I might advise one to be prudent in their pursuit of element 79. In a sense, it is the most toxic element on the periodic table — not to the body, but to the soul. Many minds throughout history have said as much, from the ancient Greek playwright Aristophanes to Brant Parker and Johnny Hart’s newspaper comic, The Wizard of Id. For my money, though, no one has expressed the sentiment better than Samuel Johnson in Irene, Act I, Scene I:

The lust of gold succeeds the rage of conquest;

The lust of gold, unfeeling and remorseless!

The last corruption of degenerate man.”

So good luck and stay safe as you search for the perfect sample of gold. I wish you success in rounding out your element collection, but also heed the warning Midas beckons from history: Be careful what you wish for.

Thanks for listening to The Episodic Table of Elements. Music is by Kai Engel. To learn how big a lump of all the gold would be, visit episodic table dot com slash A u.

Next time, we’ll catch up with mercury.

Until then, this is T. R. Appleton, reminding you, as Terry Pratchett once did, that practically everything is worth more than gold. You, for example. Gold is heavy. Your weight in gold is not very much gold at all. Aren’t you worth more than that?

Sources

- They both lived in Germany in the 1930s, and they were both winners of the Nobel Prize. That honor comes with a cash prize of ten million Swedish krona, a diploma, and a solid gold medal 66 millimeters across.1The Nobel Prize, The Nobel Prize Amounts. April 13, 2021.

- Medievalists.net, When Gold Was Medicine.

- Applied Optics, Atmospheric Refraction: A History. Waldemar H. Lehn and Siebren van der Werf, September 1, 2005.

- Encyclopedia Britannica, Tycho Brahe. Olin Jeuck Eggen, last updated January 28, 2021.

- LiveScience, Tycho Brahe Died From Pee, Not Poison. Megan Gannon, November 16, 2012.

- SAO NASA/ADS, Refraction In Tycho Brahe’s Small Universe. K. P. Moesgaard, 1988.

- io9/Gizmodo, The Crazy Life And Crazier Death Of Tycho Brahe, History’s Strangest Astronomer. Alasdair Wilkins, November 22, 2010.

- Mental Floss, Tycho Brahe: The Astronomer With A Drunken Moose. Mark Mancini, May 9, 2013.

- NCAR High Altitude Observatory, Tycho Brahe’s Observations And Instruments.

- Gaither’s Dictionary Of Scientific Quotations, p. 616. Edited by Alma E. Cavazos-Gaither and Carl C. Gaither, 2012.

- Naked Capitalism, What Is Debt? — An Interview With Economic Anthropologist David Graeber. Yves Smith, August 26, 2011.

- Bella Caledonia, The Myth Of The Myth Of The Myth Of Barter And The Return Of Armchair Ethnologists. John Alexander Smith, June 8, 2016.

- Oldest.org, 7 Oldest Coins That Ever Existed.

- The World Almanac, The Second-Oldest Profession? Andrew Steinitz, November 30, 2007.

- Connections, episode 2, “Death in the Morning.” James Burke, 1978.

- Web Elements, Gold: The Essentials.

- Etymonline, Soldier.

- My Gold Guide, A Brief History Of Gold In Roman Civilisation. October 22, 2018.

- Goldfields Guide: Exploring The Victorian Goldfields, The Welcome Stranger Gold Nugget. March 4, 2018.

- BBC News, Welcome Stranger: World’s Largest Gold Nugget Remembered. Johnny O’Shea, February 5, 2019.

- The Conversation, How Gold Rushes Helped Make The Modern World. Benjamin Wilson Mountford and Stephen Tuffnell

- Real Clear History, 10 Gold Rushes You Should Know About.

Now I kind of wonder how big the Gold Cube would be compared to other metals… and whether Rhodium’s rarity outweighs its lower density compared to the period 6 transition metals(seriously, best I’ve been able to find out, the ten densest elements are either period 6 transitions or the Outer Planet triplets… I also wonder how big an Octahedron of all the world’s carbon would be… and I just got the mental image of taking the Gold Cube and the World Diamond to make a ring worthy of a cosmic horror that snacks on star planets.