Podcast: Play in new window | Download

The periodic table shows the natural patterns and trends among the elements. Bismuth does not abide.

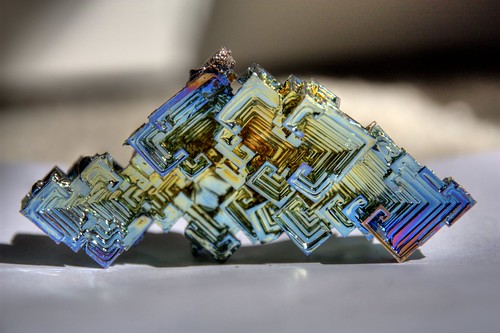

Featured above: Right angles are uncommon in nature, but bismuth is an anomalous element.

Show Notes

You know the deal — even with the extra week, I’m flying by the seat of my pants. Come back later for sources and more show notes. For now, though, here’s that promised video, and one of the print ads for Pepto-Bismol.

A team of French physicists went to great pains to measure bismuth’s rate of decay back in 2003 as part of their search for dark matter.

Episode Script

Technically speaking, lead is the last stable element on the periodic table. After 82, every isotope of every element is radioactive to some degree.

But like I said, that’s true in the technical sense. Bismuth, element 83, is radioactive… with a half-life more than a billion times longer than the age of the universe, approximately 2 × 1019 years.1 2 Put another way, if a 100-gram sample of bismuth-209 were present at the beginning of the universe, 99.9 99 9999 grams would remain today.3 It may occasionally release an alpha particle, but for all practical intents and purposes, bismuth is the heaviest stable element.

That stability is very much in keeping with element 83’s character. As we stroll through one of the roughest neighborhoods on the periodic table, we can rely on good old bismuth to keep our minds — and our stomachs — at ease.

You’re listening to The Episodic Table Of Elements, and I’m T. R. Appleton. Each episode, we take a look at the fascinating true stories behind one element on the periodic table.

Today, we’ll think about that pink drink — not zinc! It’s bismuth.

Much like zinc and molybdenum, humanity was putting bismuth to use for centuries before we realized it. It was another one of those elements that people thought was a variety of lead, due to its weight, color, similar melting point, and tendency to be found alongside actual lead deposits. This may be where its name comes from — German “wis mut,” or “white mass,” later Latinized to “bisemutum” before becoming the name it is today.

It appears that the Incans may have figured out the truth of the matter well before the rest of the world. In modern-day Peru, archaeologists found a knife with a handle containing around 18% bismuth. The blade itself contained far less, and the weapon displayed none of the brittleness that bismuth alloys usually do, indicating that the composition seems intentional.4

Over time, some of the most recognizable names in the history of chemistry started to suspect that this was something unique. Basilius Valentinus, Georgius Agricola, and Carl Wilhelm Scheele were among them, but it wasn’t until 1753 that Claude François Geoffroy demonstrated that bismuth was an element in its own right.

Based on its location on the periodic table, you might expect bismuth to be highly toxic. It falls directly below phosphorus, arsenic, and antimony in group 15. As a member of period 6, it is immediately preceded by mercury, thallium, and lead — each of those being a toxic heavy metal. In the next few episodes, we’ll see how polonium, astatine, and radon can each deliver a lethal dose of radiation.

Yet the danger presented by bismuth is practically nil. You’ve already heard about its radioactivity — or lack thereof. It also demonstrates low solubility, that is, the tendency for one substance, a solute, to break the bonds holding itself together and form new bonds with the chemical it’s immersed in, a solvent. Most of the time, the resulting mixture is the same state as the solvent. For instance, sodium chloride breaks apart in water, and the NaCl bonds with H2O in a liquid mixture.

Bismuth doesn’t do the same thing, though. When ingested, bismuth maintains its molecular cohesion and passes through the body practically untouched. Certain compounds of bismuth can be poisonous, but not the raw element.5

Plenty of chemicals are insoluble, but bismuth displays one very rare and curious behavior: When melted bismuth solidifies, it expands, just like water does when it turns into ice. This is extremely weird!

We don’t really appreciate how strange this is because water is so common on Earth. It doesn’t strike us as odd that ice floats atop liquid water. But almost anything else you can name does the opposite — for instance, when molten gold solidifies, it condenses, taking up a little less space upon solidifying. The fact that water does the opposite is absolutely critical for all life on Earth — and possibly life elsewhere in the universe, too.

If frozen water were more dense than liquid water, icebergs would sink to the bottom of the sea. The cold, dark sea. Ice formed at the surface would pile up on the ocean floor, lowering the temperature down there, far from the light of the sun. Eventually, it’s feasible that all the planet’s lakes, rivers, and oceans would completely freeze, from shore to continental shelf.

It’s hard to imagine how life could develop in a place where all the water is locked away in eternally motionless solid form.

That’s water, though. If bismuth contracted when it solidified, the universe would probably be much the same as it is today. But bismuth’s expansion does make it handy in certain situations. For instance, liquid bismuth poured into a mold will squeeze into all the tiniest nooks and crannies as it solidifies, producing a highly faithful replica of the original. Typesetters were among those who exploited this property to great effect, casting sharp, finely detailed letters for use in their printing presses.

Bismuth’s most common and widespread use, has nothing to do with those qualities. You’ve probably encountered it if an upset stomach ever gave cause for you to swallow an impossibly thick, chalky, pink liquid. Yes, bismuth can be found in drugstores worldwide as Pepto-Bismol.

Bismuth has been used as medicine in some capacity since at least the 17th century — not necessarily an effective medicine, but medicine nonetheless — but it wasn’t until 1799 that people realized the brittle metal can soothe a sore stomach. At the turn of the twentieth century is when a formulation similar to today’s medicine hit the shelves, and it is here that I’d like to pull back the curtain just a bit.

When researching an episode, I’ll usually search for the people involved with its discovery and use to see if they have any interesting stories. Often, digging down on a subject will reveal a story even more riveting than the more famous one I found in the first place.

I ran into a snag when looking up Pepto-Bismol, though. Sources recorded the time and location of its invention, but no names. Not even an attempt at a name. The best description I could find was that the formula — then called Bismosal — was invented “in 1901 by a doctor in New York [state].” None of these sources even seemed concerned with that doctor’s anonymity; it was completely glazed over. From books to blogs, even peer-reviewed research papers, the creator was only ever called out as “a doctor from New York.”6

I suspect a lot of this comes from writers taking information from a single prevalent source. One prominent article becomes the basis for blog posts and videos on the subject, which go on to inform further works. Eventually search engine algorithms index a particular tidbit and serve it up as a true fact, which helps that information proliferate even more, regardless of validity.

Using a primary source usually mitigates the issue by getting information straight from the horses mouth, whoever the horse happens to be. It’s often harder to track these down, but well worth the effort.

In this case, even Pepto-Bismol’s own website refers to the creator as “a doctor” on the company history page. (For the record, I would not consider a company’s website to be a valid source on its own history, but sometimes it can provide breadcrumbs to follow further down the research trail.)

So, alas, whoever first concocted Bismosal surely lived a rich life full of fascinating stories, but I can tell you none of them. All we know is that they created the medicine in response to cholera.

Cholera was one of the world’s deadliest diseases, and remains so in many parts of the world. Outbreaks are usually caused by a water supply tainted with human waste, humans seeming to be the only animal capable of carrying the bacteria. It kills tens of thousands of people every year, with children being especially susceptible.

One of the main symptoms of cholera is intestinal distress, especially diarrhea that can cause life-threatening dehydration. Providing a weapon against this disease is, supposedly, what motivated “a New York doctor” to create and sell the pink and minty medicine.

Bismosal might have actually been more of a detriment than a help in the fight against Vibrio cholerae, but the mixture of bismuth and aspirin was effective at combating its torturous symptoms, and quickly became a common remedy for less severe ailments ranging from traveler’s diarrhea to hangovers.

Pepto-Bismol is one of those very rare medicines invented over a century ago that wasn’t eventually found to be some kind of addictive narcotic, deadly poison, or just plain ineffective junk, so you can still buy it today. In fact, unlike its chemical neighbors on the periodic table, there’s a decent chance you already keep a bottle of the stuff in your home.

That would make a fine sample for your collection, but those who put in the extra effort to procure a pure crystalline sample are rewarded with something beautiful and unlike any other element: dizzying stairways of repeating fractal squares boasting a rainbow sheen caused by a thin layer of bismuth oxide.7 Many element collectors consider it a must-have because of its unique and alien beauty. Personally, I agree.

It’s not difficult to find a vendor who sells these crystals, but you can also grow them at home. In my opinion, that’s much more rewarding — and cheaper — than simply purchasing a sample ready for display. Why don’t we find out how? It’s been a while since we’ve done an experiment, anyway.

Naturally, you’ll need to get your hands on some bismuth. It’s actually not commonly used for household products. It’s an ingredient in some cosmetics and paints, lead-free fishing sinkers, and electrical components like solder and fuses. It’s often used to create alloys with low melting points, like Wood’s metal, which we heard about in episode 48.8

Wood’s metal is often found in fire safety sprinklers, the kind often found on the ceilings of commercial buildings. The bismuth alloy securely stoppers the sprinkler… until the room starts heating up. It doesn’t take long for a fire to bring the temperature to 70 degrees Celsius (158 degrees Fahrenheit), at which point the stopper melts and the sprinkler starts sprinkling. Rather clever.

None of these makes for a very good supply of element 83, though. It would take hundreds of sinkers and sprinklers to acquire enough bismuth for this to be worth your while. Besides, while bismuth is non-toxic, Wood’s metal contains a fair bit of lead and cadmium, making it quite toxic. You probably shouldn’t tamper with lifesaving equipment anyway.

“But wait,” I hear you exclaim. “Why don’t we extract it from readily available Pepto-Bismol?”

Well, you can, but it too would be a relatively ineffective method for this endeavor. Starting with four boxes of Pepto-Bismol tablets will only yield a coin-sized amount of bismuth. Actually, that would be a pretty cool way to add bismuth to your collection, so I’ll post a YouTuber’s how-to video at episodictable dot com slash bi. To grow crystals, though, we’ll need a lot more of the metal than that.

Plus, we need bismuth that’s very pure, ideally at least 99.99% pure. Contaminants will inhibit crystallization, so using any of the aforementioned sources will likely result in disappointment.

Your best bet is probably to just purchase a couple pounds of the purest bismuth you can find from an online seller. I don’t like recommending this, because honestly, you could buy pure samples of most of the elements online if you were so inclined. But as your humble host, I believe that spending a few thousand dollars on eBay must be the most boring way to collect the elements. Obviously, you are free to disagree.

Besides, we’re creating something new out of that pure bismuth anyway, so we’re still working for it.

Now, if you’re going to perform this experiment, you must take some basic precautions. I recommend at least wearing eye protection and work gloves, because we will be dealing with some extremely hot molten metal. Additionally, if you melt your bismuth in a pot, make sure it’s a pot you’ll never use to cook food again.

With safety addressed, you can proceed with what’s actually a very simple procedure. Place your bismuth ingots in the pot and put it on the stovetop. Turn the vent on, or at least open a window, and heat on high. For a long time, it’s going to look like nothing is really happening. Just wait. After about twenty minutes, the metal will start to liquefy.

Once all your bismuth has melted down, wait for a thin layer of film to form on the top. Skim this off, then turn the burner to low. We want the metal to cool down as slowly as possible to allow the formation of large, intact crystals.

When the top of the bismuth looks like it’s starting to freeze over, that’s a good time to pour the remaining liquid into another container you don’t care about. Set this aside if you’d like to grow more crystals later, or just to have a sample of non-crystalline bismuth. What remains in your pot should be an impressive bed of iridescent crystals. After everything cools down, you can safely remove that from the pot. A few good thwacks to its underside should do the trick.

A pair of tin snips can help you prune the largest crystals off, or you can simply break them apart. Bask in the satisfaction of what you’ve done and find an appropriately prominent place to show off your creation.

As for what to do with the remaining bismuth, well… have you considered taking up amateur typesetting?

Thanks for listening to The Episodic Table of Elements. Music is by Kai Engel. To see some amusing vintage ads for “the pink business,” visit episodic table dot com slash B i.

Next time, we’ll return to the Danger Zone with polonium.

Until then, this is T. R. Appleton, reminding you that if cholera is not a pressing concern for you, it’s probably thanks to chlorine.

Sources

- Physics World, Bismuth Breaks Half-Life Record For Alpha Decay. Isabelle Dumé, April 23, 2003.

- The Royal Society Of Chemistry, Chemistry In Its Element: Bismuth. Andrea Sella.

- Chemicool, Bismuth Element Facts. October 15, 2012.

- The Christian Science Monitor, The Incas’ Ingenious Metalsmiths. Robert C. Cowen, February 16, 1984.

- Emergency Medicine News, Bismuth Toxicity, Often Mild, Can Result In Severe Poisonings. Joseph R. DiPalma, April 2001.

- Reviews Of Infectious Diseases, Bismuth Subsalicylate: History, Chemistry, And Safety. Douglas Ws. Bierer, January 1990.

- Rock & Gem, Rock Science: Bismuth — Iridescence And More. April 21, 2012.

- Cosmetics Info, Bismuth Oxychloride.

Is the Inca knife still made out primarily of copper? Also that bismuth character from Steven Universe? Do you know that character?

I believe that’s right, yes. Regarding Steven Universe, I don’t know much about it, though I hear it’s a good show! It does occasionally come up in my research due to the characters’ names, and did this time too.

Any other materials that extends on freezing?

I believe silicon, germanium, and gallium all do to some degree, and there may be a few others I can’t think of at the moment.

So, is Bismuth the last element that’s safe to handle with bare hands for prolonged periods?

Yes! Well… kind of. It depends on how comfortable you are with ionizing radiation. We’ll certainly need to get a little creative to collect our samples from here on out.

Hi TR.

Enjoying the progress through the table.

Thanks for your work.

Kindest regards to you and the family.

Stay safe.

Hadrian.

Melbourne.

Hi Hadrian, it’s so nice to hear from you again! And glad you’re enjoying the program. Just one more period left!

Me and mine have been fortunate over the past year. I hope the same is true for you and your family down in Melbourne.

All the best!