Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Many episodes have incorporated geology, but this one is more about geography. (And amateur nuclear science.)

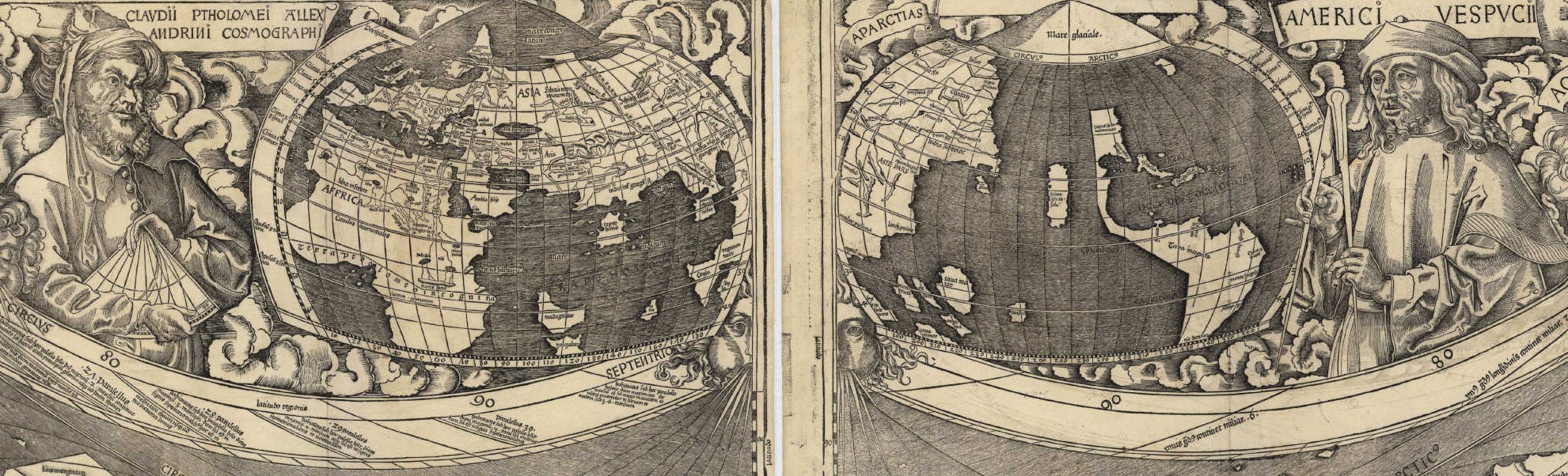

Featured above: Two legends of geography — although only one of them appears on the periodic table of elements.

Show Notes

The Sounds of Seaborg: If you hear that Quiz Kids audio anywhere else, it’s likely to sound a little different from what you heard in this episode. I’ve found that a lot of audio recorded in the first half of the twentieth century sounds, well, kind of wonky. Often this is because audio equipment at various stages of the recording, mastering, and archival processes didn’t all match up perfectly, leading to a recording that’s a little too slow or too fast. The Quiz Kids clip was too fast. That has the additional effect of making everyone sound kind of like a chipmunk.

That same artifact exists in the famous audio clip of the Hindenburg disaster, which was actually featured in Episode 1 of this very program. I regret that I didn’t alter the audio in that episode, because I think it’s much more valuable to hear the audio as it would have been heard in its time, in the actual voices of the speakers. So I did just that for this clip. (I also cut maybe 20 seconds of less-than-relevant chatter, and might’ve erred on the side of keeping too much.)

Who, Again? During the research for this episode, I came across a charming video of a little ditty called, “Samarsky Was Just Some Guy.” I’m a major proponent of silly science songs, so I had to share it here. Plus, it looks like the creator might’ve listened to this podcast — so if you’re reading this, bravo!

The ID of Venus; I mentioned Amerigo’s cousin-in-law who was a model. Her name was Simonetta, and some sources claim she is the main subject of Botticelli’s painting, The Birth Of Venus. That seems difficult to substantiate, though, so I didn’t include that in the script.

Lost in Chorography: I lost a couple days on this script because I wound up writing a whole bit about chorography, another way people used to communicate geography, but it turned out to really not be a great fit for the episode. I think it’s still interesting, though, so to prevent it from going totally to waste, here’s some of that.

Chorography was interested in conveying an almost-emotional impression of a region, more likely to incorporate landscape paintings than precise maps. Ptolemy wrote that “Chorography deals above all with the qualities rather than the quantities of things … it attends everywhere to likeness, and not so much to proportional placements.”1 In other words, a lesser system that required no particular skill.2

On the other hand, Ptolemy saw map-making as grand in scale and highly mathematical — the division of the entire world into precisely measured and coordinated chunks of a geometric plane. “Mathematical method … takes absolute precedence,” he wrote.

It appears that Ptolemy was able to set his biases aside, however, because The Geography consists of both cartography and chorography. Thus, with both art and empiricism, Ptolemy described the entire world as known to second-century Greco-Roman civilization. This was called “the ecumene,” and encompassed Europe, Asia, and Africa. His work was so detailed, and so thorough, that it remained the best source on the material for well over a thousand years.

…

Renaissance philosophers didn’t agree with Ptolemy on everything, though, because chorographies also became quite celebrated for a time. True to the Ptolemaic definition, these were literary works of art, fully describing the topographical, cultural, and mythological history of a locale in prose and poetry. As the chronicle was an account of a time, chorography told the story of a place. Together they provided the foundations for historical study, especially among Renaissance high society.

Colum-Busted: Columbus needed to be “bringing Christianity to uncivilized peoples,” but also couldn’t enslave Christians. So he had an incentive to characterize indigenous people as “irredeemable.” (The word “cannibal” itself comes from a Spanish misunderstanding of the Carib people’s word for themselves!) Ferdinand and Isabella were practically begging Columbus to stop enslaving people and just look for gold and pearls, but he kept sending back boats full of enslaved people, saying, “Hey, yeah, still working on the gold, but surely you could fetch a good price for all these slaves!”

In 1500, his behavior was so objectionable that a royal commissioner was sent to find him on Hispaniola and arrest him. He was sent back to Spain in chains. And there were many, many other atrocities he committed. Bartolomé de las Casas wrote eyewitness criticism of him, as did some of his crew, but even Columbus’s own journals show that he was involved in some terrible, terrible practices.

But I wound up cutting most of that from the episode, since it wasn’t directly relevant to this story, and I’m hoping that much of this information is well known by now.

Not Much Arable Land Down There, Though: It is possible that Polynesian explorers found Antarctica over a thousand years before its modern discovery. A monumental 7th-century Polynesian explorer named Ui-te-Rangiora went on some legendary expeditions. He is purported at one point to have visited a southern sea where rocks “grow out of the sea like arrowroot.” Some have taken this to mean he found Antarctic ice floes. Intriguing, and exciting to think about!

However, the evidence is poorly substantiated, and this interpretation relies upon some heavily motivated reasoning. The described phenomenon could just as easily be referring to sea foam (arrowroot can fizz upon contact with water), or floating pumice stones from some volcanic explosion, or something else entirely.

Don’t Fear The Ursus: As linguaphiles know, the Arctic region takes its name from the Greek and Latin words for “bear,” referring to the constellation Ursa Major in the northern sky. Apparently this was a florid way to refer to heaven in Middle English, but took its modern meaning during the Renaissance. Thus “Antarctica” kind of means “Opposite to the land of the bear.”

Incidentally, “bear” — at least in English — is not the word that Germanic languages originally had for the brown beastie. Whatever that word was has been lost to history, because centuries of superstition warned that calling it by name might accidentally summon the thing right then and there. Not wanting to become lunch for woodland megafauna, hunters (and people in general) took to referring to it as, well, “the brown beastie,” and that’s where the English word “bear” comes from. The same phenomenon exists in other languages — the Russian medved, for instance, roughly means “honey-eater.”

Speaking Of Name Strangeness: “Amerigo” descends from the Germanic name “Emmerich,” making it cognate with other common European names, like Heinrich and Henry. (“Enrico” is a later Italian version of the same name, so Fermi and Vespucci have more in common than it appears at first blush!)

This also kinda means, since “America” was the deliberately feminized version of the name, that I’m writing these show notes within the “United States of Henrietta.”

(You could take this to absurd lengths and claim that the full name means “Henrietta’s Onion Stand,” but this involves several bad-faith etymological back-constructions, so you’ll hear no such claims from me.)

No Relation: David Hahn was not related to Nobel Prize-winning German radiochemist Otto Hahn in any known way. And sadly, his story did not end very well. He had trouble finding his place, and he died shortly before his 40th birthday. Maybe it’s just because my own is approaching later this year, but I can’t help but notice that being a consequential age for characters in today’s episode!

Not The Worst Thing That’s Ever Happened With Kitty Litter: While writing the script, I came across this video about a catastrophe at the WIPP. If you were gripped by the talk of nuclear waste and methods of its disposal in recent episodes, this is an entertaining watch!

Episode Script

Of all the chemical elements, number 95 might be the one whose name sounds least similar to its namesake. You might’ve not even realized that americium is named after America — changing those last few letters really sends some big phonetic changes rippling through the rest of the word.

And for what? Yet another nationalistic name on the periodic table? Eh, not exactly. Glenn Seaborg suggested the name because of its position directly below europium, thinking there was a nice continental symmetry there. And that’s fine, I guess, except for what could have been.

See, americium had a different working title. Much like the rare earths, members of the actinide series can be incredibly difficult to isolate. Elements 95 and 96 required more than a year of painstaking labor to separate from each other, causing frustrated scientists like Tom Morgan to call them “pandemonium” and “delirium,” respectively.

A bit cheeky? Perhaps. But I’m frankly astonished to find yet another element with etymological connections to Hell — even if that name didn’t quite make the final cut.

You’re listening to The Episodic Table Of Elements, and I’m T. R. Appleton. Each episode, we take a look at the fascinating true stories behind one element on the periodic table.

Today, we’re planting our flag upon americium.

The past few elements have had some real cloak-and-dagger origin stories, making this element’s reveal all the more surprising by comparison.

In the 1940s, a Chicago radio station aired a program called Quiz Kids. It was exactly what it sounds like: a collection of uncharacteristically charismatic kids would answer consistently confounding questions. Perhaps an unremarkable premise now, but it was one of the first shows of its kind to air.

Seaborg was the show’s special guest on November 11, 1945 — the day celebrating the end of World War I, and mere weeks after the end of World War II. A slightly edited excerpt of that program follows:3

Because the whole world is rightfully curious about the atomic bomb, and its grave implications for world annihilation, it seems a very appropriate subject for our Armistice Day discussion. And now I have the honor to introduce Dr. Glenn T. Seaborg.”

“Thank you, Mr. Kelly. When I was invited to take part in your Armistice Day program, I said I would on one condition: That I was not in competition with the Quiz Kids.”

“Richard, how about your question?”

…

“Have there been any other new elements discovered, like plutonium and neptunium?”

“Uh, well yes, recently there have been two elements discovered, elements with atomic numbers 95 and 96. Out at the metallurgical laboratory here in Chicago. So now you’ll have to tell your teachers to change the 92 elements in your schoolbooks to 96 elements.”4

Apparently, many young viewers in the audience did just that. Responses from educators typically ranged from incredulity to annoyance.

Element 95 is another member of the select group of atoms that are indirectly named after a person, like gadolinium and samarium. You may remember that those two took their names from their source minerals, which were in turn named after a prominent scientist, and, some guy who was nice to a geologist one time, respectively. By comparison, today’s subject has an unusually grandiose lineage.

For starters, americium is named after a much, much larger rock. This one is a whole continent — two of them, actually. And, as schoolchildren on those rocks learn every year, they are named after one Amerigo Vespucci.

When faced with the inevitable curiosity around who this Vespucci man was, and his contributions to society, my own teachers said that he was more or less “just some guy,” and lending his name to the map was the only deed of note he ever committed.

That’s kind of true, and kind of not. It’s true that he never accomplished anything more significant than eponymy — but that’s an enormously high bar for “significance.” He was quite well known and highly regarded in his own time — that being the very reason for said eponymy. But if we want to really appreciate what’s going on here, we have to go back quite a ways.

Claudius Ptolemy was an astronomer, musician, mathematician, poet, and all-around impressive fellow. You might know him as the person who popularized the theory of geocentrism, that the sun travels around the Earth. Now, it’s true, that is one of history’s most famous examples of erroneous science, but it’s not really Ptolemy’s fault the idea overstayed its welcome. Besides, he also explained the mathematical underpinnings of musical harmony, contributed plenty of better ideas about astronomy, and advanced understanding of the eyes and sight.5

But most relevant to our topic today is the fact that Ptolemy literally wrote the book on geography: Geōgraphikḕ Hyphḗgēsis, or simply, Geographia. This was the most complete work on the subject ever written up until that point — and for a very long time after. Within its pages, Ptolemy provided high-quality map projections, and invented the very idea of latitude and longitude. In exhaustive detail, he described the Earth to the furthest extents possible — from the British Isles to Malaysia, from the Canary Islands to China.

For over a thousand years, Ptolemy’s work was a foundational text for map-makers, navigators, and travelers of all types. Muslim scholars consulted it for centuries, but interestingly, Europeans had little appreciation for The Geographia for quite some time. It wasn’t until a popular Latin translation was published in the 15th century that they took a real interest in Ptolemy — but when they finally did, it was a fervent interest.

At the time, Florence was a hotbed of early humanist thought. The Geographia was admired among that set for its empirical approach and anthropocentric perspective, and its rediscovery practically kicked off the modern art of cartography in Europe.6

Amerigo Vespucci was born to one of these Florentine families in 1454, a family with priceless political connections — particularly with the de’ Medicis, one of the most powerful dynasties in European history. Amerigo’s brother was influential within the Catholic Church, and his cousin’s wife was a popular model, posing for all the greatest Florentine painters, including Sandro Botticelli.7 8

Amerigo himself was personally tutored by his uncle, Giorgio, who was a Dominican friar and prominent scholar. He made sure his student was thoroughly fluent in matters goegraphical, philosophical, rhetorical, and literary.9 As a young man, he accompanied an older cousin on a diplomatic trip to Paris, with stops in Bologna, Milan, and Lyon, and this really cemented his love of travel.

This love would go unfulfilled, though. The diplomatic mission was not a success, and when Vespucci returned to Florence, he was unemployed.10 His father died two years later, leaving him responsible for his family’s finances.11

He got a gig as the manager of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici’s household. He spent his time planning parties, running errands, and solving any pesky little problems that might pop up for Lorenzo. He held a fair bit of power this way, but the work kept him mostly tethered to Florence. He didn’t get the opportunity to travel again until he was almost 40 years old — but oh, what an opportunity that turned out to be.

The Medici were pioneers of early capitalism, among the first in history to conduct organized business on an international scale. In the early 1490s, that involved several burgeoning enterprises in Seville, España.12 But as the head of the family, Lorenzo de’ Medici couldn’t attend to that firsthand — his presence was required at home in Florence, and Seville is over two thousand kilometers away.

So Lorenzo sent a representative, perhaps the person he trusted most outside of blood relatives: Amerigo Vespucci.

This was a considerable shake-up for Vespucci. No longer was he orchestrating seating arrangements for fancy banquets, nor overseeing the household’s wine deliveries. He was negotiating contracts, handling letters of credit, and directly managing funds for trade and investment. He had considerable autonomy, acting as the regional manager for Medici interests in shipping, ship-building, and the slave trade. He managed maritime logistics and shipping routes, and worked with business partners from myriad cultures, often speaking multiple languages. Vespucci was more than a trusted ally; he was a man of many talents.

It was also an exciting time for him, personally. He arrived in Spain just in time to see Christopher Columbus embark on his first transatlantic voyage, and followed the news of his return with fascination. His business partner actually became a principal investor in Columbus’s later expeditions, and Vespucci himself provisioned some of those very ships.13[14 It only natural when Spain’s King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella finally asked him to join a voyage as a navigator, cartographer, and scientist. It was the greatest opportunity in history for someone who had dreamt of travel for so long — and an opportunity that must have seemed impossibly out of reach only a few years prior.

On May 18, 1499, three caravels set sail from Cádiz, and Vespucci was among their crew.15 16 Two years later, the Portuguese government offered him another such opportunity, so twice he crossed the ocean and back again.

These expeditions were concerned with finding a new route to Asia. Initially, Vespucci himself was hoping to establish lucrative and exclusive trade relations with India.17 18

But along the way, Vespucci started to notice that the math wasn’t adding up. The stars in the night sky were all wrong, and so were the currents of wind and water. When they approached land, the coastlines didn’t match anything Ptolemy had described in Geographia. Eventually the Europeans clambered ashore, where they encountered plants and animals and even entire civilizations the likes of which no European had ever seen. And most significantly, this land mass was vast, enormous, far too big to be a few islands off the coast of Asia.19

That’s what he told Lorenzo, at least. Vespucci wrote to his Medici patron at length about his adventures. In 1503, he sent a letter describing the highlights of his recent tour with the Portuguese, and opened with a bold claim: These newly explored regions, he said, may rightly be called “a new world.”

“It will be a matter wholly new to all those who hear about them,” he said, “For this transcends the view held by our ancients.” Here he openly defied Ptolemy himself. He continued, “I have found a continent more densely peopled and abounding in animals than our Europe or Asia or Africa, and in addition, a climate milder and more delightful than any other region known to us…”

The letter continues in a sensational way. Vespucci included breathless descriptions of the people inhabiting the land, variously describing them as gentle and free, and debauched and barbaric. He gives special attention to the many ways they practice cannibalism, all of them outrageous and shocking.

To be clear, Vespucci was not what we’d call an “anthropologist.” He also claimed the people he encountered lived to an age of 150 years and could cure any disease with roots and herbs, so it’s clearly not a dispassionately factual account of civilization at the precise moment of the Columbian Exchange. But first and foremost, Vespucci was still a merchant, looking for mercantile opportunities. He had already been involved in the slave trade for years in Seville, and was perfectly happy to increase his profits in that sector. The subtext of passages depicting indigenous people as “uncivilized” was to say they could be pressed into slavery without qualms

That aside, his writing became quite popular. Lorenzo passed this letter around his high-flying social circle, and soon it made its way to a print shop in Paris. From there, it was circulated far and wide, a best-seller and a genuine sensation among every set.20 Over the following months it was published dozens of times, all across Europe.

He was not the first person to claim that this was a new part of the globe, but he was the first to make that case so widely. Importantly, people really liked Vespucci’s choice of words. He didn’t refer to the land by some dry technical term like a “novel hemisphere” or “the western antipodes,” he wrote about “the new world.” The term spread far and wide — even as far as Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, a remote town tucked away high in the French Alps.

Saint-Dié was an interesting little town: Directly controlled by the Catholic Church, located at the crossroads of various French, Germanic, and Swiss territories. Accessible from all of them, but independent of them. It was wealthy, but quiet.

In the early 1500s, it provided fertile ground for philosophical and scientific ideas to take root. Prominent mathematicians and cartographers assembled in Saint-Dié as the Gymnasium Vosagense, intent on publishing a new, definitive compendium of world geography. They would sift through all the exciting stories of discovery across the Atlantic, separate fact from fiction, and reconcile this new information with the time-tested topography of Ptolemy.

The work was arduous and meticulous, but in April 1507, they published a landmark: One hundred three pages of Latin text describing all the ends of the Earth and its place amongst the stars, written by Matthias Ringmann. Martin Waldseemüller created the accompanying globe and maps, including one of the entire world displayed across twelve wooden panels, totaling more than two meters wide. The entire thing was ostentatious in both style and scope. Whereas Ptolemy had written Geographia, Ringmann and Waldseemüller named their work Cosmographiae.

Their work was the first of its kind, distinctly and unequivocally displaying the newly discovered lands as continents in their own right, with an entire ocean separating them from Asia. One large land mass occupied the northern part of this new hemisphere; another occupied the south; a thin strip of land between the two. Atop the southern continent, large capital letters spell out a new name: “America.”

The text explained this nominative decision:

I see no reason why anyone could properly disapprove of a name derived from that of Amerigo, the discoverer, a man of sagacious genius. A suitable form would be Amerige, meaning ‘Land of Amerigo,’ or America, since Europe and Asia have received women’s names.” 21

According to Waldseemüller and Ringmann, Vespucci was a modern-day successor to Ptolemy, equal in brilliance and importance. Ptolemy’s maps defined the old world; Vespucci described an entirely new one. Waldseemüller adorned his map accordingly: Hovering above one half of the Earth is Claudius Ptolemy, the Alexandrian Cosmographer. Above the other half sits Amerigo Vespucci, holding an enormous compass. Both are depicted as serene, heavenly figures, surrounded by personifications of the north winds.

It might sound odd to hear Vespucci referred to as the person “who discovered this part of the world” when few people today know his name, and modern mythology unambiguously ascribes that role to Columbus. But Vespucci was the first to properly, and popularly, recognize these lands as heretofore entirely unbeknownst to Europeans.

Columbus, on the other hand, insisted until his dying day that he had visited Japan.22 23 24 And he wasn’t exactly popular besides. Now, trust me, I would love to talk about Columbus, but neither you nor I have the time. The short version is: He was widely known as a cruel, avaricious idiot. And that was his reputation in 1507, so that’s just judging him by the standards of his time. Waldseemüller was probably not looking to glorify a buffoon in his magnum opus.

Among the continents, this name is singularly romantic and humanist. Antarctica wasn’t discovered until the 19th century, but scholars had already been using the word “antarctic” for half a millennium to refer to a theoretical continent at the southernmost reaches of the Earth. From ancient Greek and Latin, that name literally means, “opposite to the North Pole.”

When Europeans first encountered the land of kookaburras, didgeridoos, and Uluru, they called it “Terra Australis,” the name for a different theoretical continent from premodern thought. (There were kind of a lot of mythical land masses back then. It had something to do with an idea that continents should be evenly distributed around the world, to balance each other out.25) Anyway, that was soon shortened to “Australia.”

The Romans named Africa after a group of people they met in the north of that continent. As Waldseemuller said, Europe and Asia do technically share names with female figures from Greek mythology, but a more compelling theory — to me, anyway — traces the continents’ etymological roots further back to Akkadian words, giving Asia and Europe names that mean “Land Where The Sun Rises” and “Land Where The Sun Sets”, respectively.

And, for the record, there are other names for the continents of the Western Hemisphere, like the Guna-language term AbyaYala.26 But far and away, the most commonly printed name for this land is the one taken from Amerigo Vespucci. By realizing where in the world he was, and writing about it in a thrilling way, he secured a prominent place on the map for centuries thereafter. He died in 1512 without ever learning what would happen to his name, and of course, there’s no way he could have known the specifics of chemical nomenclature 400 years in the future. But in this admittedly roundabout way, he became the oldest person in history to be represented on the periodic table of elements.

Some of you listening already know what I’m going to recommend to the element collectors today, because there’s really only one option when it comes to this radioactive, synthetic element. Some of you might even already know about history’s most infamous collector of americium, and it would be nothing less than podcast malpractice to create an entire episode about element 95 without mentioning the Nuclear Boy Scout.

A person like David Hahn would fall squarely within the target audience for this very program. In the early 90s, he was a curious kid, fascinated with chemistry, and he was actually an element collector before it was cool. If anything, Hahn might’ve found us a bit prudish in our approach, as he had a markedly high tolerance for risk. He wanted to collect every element, regardless of the danger — and not just for some idle display. He wanted to work with them.

Hahn was inspired by the Curies, and by Enrico Fermi.27 28 But his step-grandfather was just as influential when he gave Hahn a copy of The Golden Book Of Chemistry Experiments, a 1960 tome that helped young readers learn the fundamentals of chemistry with hands-on exercises. By then, it had been out of print for decades due to safety concerns — concerns that were probably quite valid. At one point, young Hahn caused an explosion in the basement when working with red phosphorous; another time he passed out for more than an hour after synthesizing chloroform — the Golden Book recommended “sniff[ing] carefully” to experience its “peculiar sweetish odor”.29 30

Hahn’s family nudged him to join the Boy Scouts, hoping it wold provide structure, friendships, and activities that might distract him from these hazardous pursuits. But this wasn’t just a phase. Hahn actually found a way to pursue his scientific interests within this new framework, quickly earning his merit badge in Atomic Energy. If anything, he found himself even more fascinated by radioactive materials than the simple acids and alcohols he had worked with before.

By age seventeen, he had become obsessed with nuclear reactors. Not merely as an idea — he was going to build one. By himself. Out of found materials. In his mother’s backyard potting shed.

He was resourceful, and scrappy. He acquired uranium by telling a Czechoslovakian chemical supply company he was a professor buying materials for a research laboratory. He found radium in the form of luminescent paint after his homemade Geiger counter lit up near an antiques shop.

And he sourced americium-241 from broken smoke detectors he bought by the hundreds for a dollar apiece.

Eventually, though, the project became too dangerous even for Hahn. He decided he had “too much radioactive stuff in one place” after his Geiger counter showed signs of radiation as far as five houses down the street. Piece by piece, he disassembled his nuclear machinery and started slowly disposing of it.

A bit too late, though. When pulled over by the police for an unrelated incident, officers searching his car found a toolbox full of americium, mercury, thorium, and other toxic and radioactive materials. That led them to Hahn’s backyard lab, which was quickly assessed as “beg[ging] for a controlled remediation that is beyond our authority or resources to oversee.”

By mid-1995, the EPA turned the place into a Superfund site. As Ken Silverstein described in an article for Harper’s Magazine,

After the moon-suited workers dismantled the potting shed with electric saws, they loaded the remains into thirty-nine sealed barrels placed aboard a semitrailer bound for Envirocare, a dump facility located in the middle of the Great Salt Lake Desert. There, the remains of David’s experiments were entombed along with tons of low-level radioactive debris from the government’s atomic-bomb factories, plutonium-production facilities, and contaminated industrial sites…”31

That was pretty much the end of Hahn’s atomic energy career.

But wait, what was that a minute ago, about sourcing americium from smoke detectors?

That’s right. There’s a good chance you already possess a sample of today’s element. Since the 1970s, americium-based smoke detectors have been the most popular kind due to their low manufacturing cost and their effectiveness. They’re relatively simple devices: A small lump of americium dioxide sits inside a chamber, emitting a constant stream of alpha particles that ionize the air within. That charged air allows current to flow through an electrode. When smoke enters the chamber, it disrupts that stream of particles, causing the electrode to drop the current. That’s the trigger for the alarm.

It doesn’t require a lot of americium to do this job well — only 300 nanograms, barely a tiny speck of material.32 Nonetheless, most informed element collectors would recognize a smoke detector as a valid representative for today’s subject. And if you leave the smoke detector intact, you needn’t even take any special safety precautions.

You might want to acquire that sample sooner rather than later, though. Americium-based smoke detectors are still easy to find, but they’re starting to decline in popularity. Photoelectric models, which use a beam of light and a sensor rather than the ionized air electrical circuit, are more accurate and less expensive than ever before. They’re also a lot easier to dispose of than the radioactive version, so they’re gaining in popularity. In fact, listeners in Germany and France are already out of luck. Those countries effectively banned ionization detectors several years ago.33 34 35

I’m afraid that really is the only option today for element collectors, unless you work in some highly specialized industry or research — and even if you do, any interaction with americium is likely to be bad news. Just ask Harold McCluskey.

He was one of the few people on Earth whose job was all about element 95. He worked at Washington state’s Hanford plutonium plant, recovering americium from spent nuclear fuel. One ton of waste only contains about 100 grams of the stuff, so it was delicate work — and dangerous.36 In 1976, his work exploded, dousing him in a mixture of radioactive materials, glass shards, and nitric acid. He survived the immediate disaster, but also received 500 lifetimes worth of ionizing radiation. He required months of intensive medical treatment, but he did get better.

Even after he recovered, though, he remained highly radioactive. He became known as “The Atomic Man,” and could set off a Geiger counter from 50 feet away.37 38 Former friends and fellow churchgoers shunned him, afraid that McCluskey would irradiate them, as though he had some contagious disease. On the contrary, he died at 75 years old, of entirely unrelated causes, with no signs of cancer anywhere in his body.

All the same, it’s the kind of ordeal best avoided, at least in the opinion of your humble host. Better to stick with the smoke detector.

There is something else that makes our sample of today’s element special, and perhaps a little bittersweet: It is the last element we will be adding to our collection.

I know this is difficult to hear, but we are bumping up against the twin limits of nuclear instability and biological frailty. In other words, upcoming elements simply don’t last very long, and if you got too close, you probably wouldn’t last very long either.

We’ll try some creative shenanigans in future episodes, but soon, those too will run dry. So we will try to find other ways to represent the elements in future episodes, but by and large, we must accept that our days of hunting down rare isotopes and allotropes are behind us.

But fret not, dear listener. Even if we can’t get our hands on every last element on the periodic table, there are no restrictions preventing their stories from reaching your ears.

Thanks for listening to The Episodic Table of Elements. Music is by Kai Engel. There’s a great deal in the show notes this week, from The United States of Henrietta to scary bears to a kitty litter-induced nuclear incident. To read about all that and more, visit episodic table dot com slash A m.

Next time, we’ll hear the patently absurd case of curium.

Until then, this is T. R. Appleton, reminding you that the audio clip shared earlier clearly proves that Glenn T. Seaborg did not speak with the cartoonishly exaggerated Yooper accent I lent him in the prior episode, yet I regret nothing.

Sources

I’m afraid I didn’t add all my sources inline yet! I don’t want to delay this episode any further, though, so — admittedly hastily — here are some works cited for any further research you may wish to conduct:

Sources

- Ptolemy’s Geography: An Annotated Translation Of The Theoretical Chapters, p. 58. Translated by Alexander Jones and J. Lennart Berggren, June 16, 2020.

- The Routledge Handbook of Translation and the City, this page. Edited by Tong King Lee, June 27, 2021.

- Chemical & Engineering News, Americium. Rachel Sheremeta Pepling.

- Audio via Berkeley Labs’ Soundcloud page.

- Encyclopedia Britannica, What Were Ptolemy’s Achievements? Last updated February 12, 2025.

- Stanford University Libraries Leonardo’s Library: The World Of A Renaissance Reader, Looking At Ptolemy’s Geography.

- Sandro Botticelli: Life And Work. R. W. Lightbown, 1989.

- Art Bit32-33es: Who Was Simonetta Vespucci, Botticelli’s Enduring Muse? Artnet. Tim Brinkhof, August 17, 2024.

- Amerigo Vespucci: The Historical Context Of His Explorations And Scientific Contribution, p. 32-33. Pietro Omodeo, February 1, 2022.

- p. 34.

- EBSCO, Amerigo Vespucci. Clara Estow, 2022.

- p. 32 – 35.

- Ebsco Knowledge Advantage, Amerigo Vespucci.

- The First Four Voyages Of Amerigo Vespucci

- p. 461.

- Amerigo: The Man Who Gave His Name To America, Chapter Three: The Stargazer At Sea. Felipe Fernández-Armesto, 2006.

- p. 99.

- The Life Of Amerigo Vespucci: Biography, Letters, Narratives, Personal Accounts & Historical Documents, this page. Edited by Clements R. Markham, 2023.

- The Letters Of Amerigo Vespucci And Other Documents Illustrative Of His Career. Translated by Clements R. Markham, August 3, 2011.

- John Carter Brown Library Of The Early Americas, Mundus Novus.

- Amerigo: The Man Who Gave His Name To America, “What’s In A Name?” Felipe Fernández-Armesto, 2006.

- EBSCO, Amerigo Vespucci. Clara Estow, 2022.

- Omodeo, P. Amerigo Vespucci: The Historical Context of His Explorations and Scientific Contribution, p. 178 – 179. 2020.

- The Map That Changed the World. October 28, 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/8328878.stm (accessed 2025-08-29).

- The Literary Mirroring Of Aboriginal Australia And The Caribbean, p. 21. Dashiell Moore, 2024.

- Walsh, C. E. (2015). Decolonial pedagogies walking and asking. Notes to Paulo Freire from AbyaYala. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 34(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2014.991522

- Harper’s Magazine, The Radioactive Boy Scout. Ken Silverstein, November 1, 1998.

- PBS News, If A Boy Scout Can Get Nuclear Materials, What’s Stopping Terrorists? February 8, 2011.

- The Radioactive Boy Scout, p. 17.

- The Golden Book Of Chemistry Experiments, p. 89. Robert Brent, 1960.

- The Radioactive Boy Scout, Harper’s Magazine. Ken Silverstein, November 1, 1998.

- Still, B. The unveiled states of americium. Nature Chem 9, 296 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.2733

- Budesamt für Strahlenschutz, Ionizing Radiation.

- Service-Public.fr, Smoke Detector (Daaf): Fire Safety In The Housing. Last updated March 8, 2024.

- Ordinance on Protection against the Harmful Effects of Ionising Radiation — Radiation Protection Ordinance, p.132.

- The Periodic Table: A Visual Guide To The Elements, Americium. Paul Parsons, 2014.

- The New York Times, FOLLOW-UP ON THE NEWS; ‘Atomic Man’. Richard Haitch, June 27, 1981.

- Atomic Harvest: Hanford And The Lethal Toll Of America’s Nuclear Arsenal, p. 220. Michael D’Antonio, 1993.

Note this is the first atom that cannot found in nature, at least in Earth. Element 95 and higher can possibly form in neutron star collisions and supernovae, but they’re undetectable due to small amounts; possibly also present in neutron star crusts.

BTW, when we get to the superheavy main group metals? Also upcoming elements named after people indirectly?

I should look it up before speaking definitively, but I believe the “superheavies” are those beyond the actinide series. As far as when we’ll get there, hm. Stay tuned!

We have another indirect honor coming up the episode after next, with berkelium.

The other indirect honour element is livermorium?

When we will talk about decay chains and the Goldschmidt classification?

Also is transactinide another word for superheavy elements?

Have you’ve seen old periodic tables that had roman numerals from I to VIII? There were two naming systems: CAS and IUPAC.

Off the top of my head, I’m not sure I’m able to answer those questions, except for: transactinide and superheavy do seem synonymous; and, not only have I seen those tables with roman numerals at the top, but the periodic table I used in high school included that numbering system! (It also had several elements with placeholder names, like “Ununbium,” with symbols like “Uub.”)

Some of the textbooks from my time in school(I graduated HS in 2005) had tables that only went up to 109 and only had proper names up to I think 103 with systematic names like unnilquadium and unnilpentium for the period 7 D-block elements… though a little googling informs me elements 104-109 were officially named in 1997, the year I turned 11 and entered the fifth grade… Google is failing me for when elements 102 and 103 were named and I’m too lazy to search the wikipedia articles for those bits of trivia… Wild to think that a eighth of the periodic table has been named in the last 30 years… and that eighth isn’t even half of the seventh period.

Great job, really like this podcast!

When you said:

“There is something else that makes our sample of today’s element special, and perhaps a little bittersweet: It is the last element we will be adding to our collection.”

I was saddened at first because I thought you meant the podcast series was over. Thankfully you just meant the remaining elements will not be collectable.

Note. I think Americium-based smoke detectors would also be an easy way to add a tiny amount of Neptunium to your element collection. Because Americium-241 (half life of 432 years) decays to Neptunium-237 (half life of a couple million years). I think about 1% of the original Americium in a smoke detector will have decayed to Neptunium after 5 years.

I’m glad it wasn’t too harsh a rug pull! And indeed, I think you’re quite right — and that’s precisely the sort of “shenanigans” I was referencing in that segment, as well. You’re ahead of the curriculum!

What a joy to hear from you. Thanks for another interesting, educational, humorous podcast. On tallying another birthday-zero soon, congrats and every good wish.

It’s a joy to create the program, particularly and especially when I have such dedicated listeners. (And readers!) Thank you so much, Leynia.

Another Episode! Glad to see that you’re still going after so many years : )

I first heard Ptolemy though Ptolemy Theorem in geometry, quite a useful theorem for competition math actually: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ptolemy%27s_theorem

PS: I’m not sure if this is a bug on my end, but the episode archive page looks glitched on my computers and tablets, you might want to take a look.

I am so happy for another podcast.