Podcast: Play in new window | Download

From giant prehistoric sharks to clandestine Cold War projects, manganese is an element that has concealed a lot of secrets.

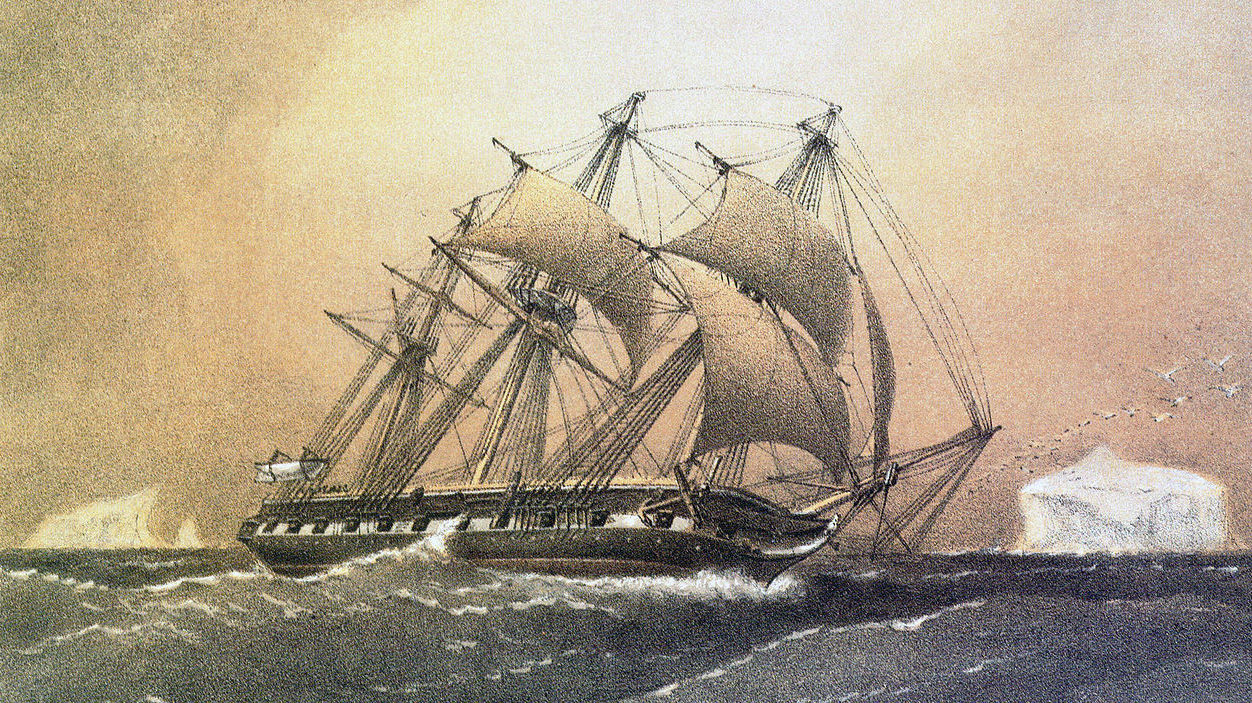

Featured above: A painting of the HMS Challenger by William Frederick Mitchell.

Show Notes

I’m currently traveling for the Thanksgiving holiday, so I’m light on show notes this week, unfortunately! I’m hoping to get them written up sometime this week. Thank you for your patience!

Episode Script

In episode 12, we learned that magnesium is often found cavorting with manganese, and indeed, that’s the reason their names are so similar. We also learned that magnesium plays a critical role in plant life, with one atom of that element being the linchpin of every molecule of chlorophyll.

Sure enough, manganese is right there, too. It’s not a part of chlorophyll, but it plays an important structural role, allowing plants to grow tall and woody, and it’s just as important in the chemical reactions that allow plants to convert water into carbon and oxygen.1

It also happens to be a difficult element for most life forms to digest — except for fungi, which can tear right through it with little issue. This means manganese is pretty important for fungal biology, too. But strangely, it’s also at the heart of maneb, one of the more effective fungicides yet discovered.2

This little back-and-forth that manganese enjoys in the circle of life is all quite droll, but not exactly a thrill a minute. That’s only because we’re looking at dry land. As we’ll see, things get much more interesting once we shift our gaze beneath the waves.

You’re listening to The Episodic Table Of Elements, and I’m T. R. Appleton. Each episode, we take a look at the fascinating true stories behind one element on the periodic table.

Today, we’re cracking the case of manganese.

In 1858, the United Kingdom’s Royal Navy launched the HMS Challenger, a Pearl-class corvette with three masts and a supplemental steam engine that could nearly double its speed. The ship saw combat off the coasts of Mexico and Fiji, and at one point was Australia Station’s flagship. Clearly the Challenger was a notable little ship, but its real claim to fame came after all that, when it was chosen to lead the world’s first voyage of scientific discovery.3

The expedition was spurred by a newfound curiosity of the ocean floor, especially because widespread adoption of telegraph machines was creating demand for transcontinental cables. So on December 21, 1872, 243 officers, scientists, and crew embarked on a four-year mission to boldly go around the world, collecting enough data to write nearly 30,000 pages of reports and colorful illustrations of never-before seen life forms.4

The primary method of data collection was almost laughably straightforward: The crew would take a bucket, tie it to a really long rope, and scrape it along the sea floor for a while before pulling it back up. This approach worked all over the world, even along the deepest known floor of the ocean, a location that has borne the name Challenger Deep for nearly 150 years in honor of the ship that discovered it.5

Curiously, no matter where they sailed, the crew kept dredging up bumpy blue rocks, about the same shape and size as a potato. They’d sometimes retrieve dozens of them in a single haul. Analysis performed by the ship’s chemist, J. Y. Buchanan, showed that these rocks were composed of almost pure manganese peroxide, and so they’ve come to be known as manganese nodules.

The Challenger crew didn’t happen to stumble upon a mother lode of manganese. Modern data suggests that the ocean floor could be littered with half a trillion tonnes of these little sea potatoes.

Where could they possibly be coming from? This is actually a mystery that was solved shortly after their discovery, by the scientists on board the Challenger. All they had to do was crack them open.

They found that these nodules all formed around some kind of core and slowly built up over time. Sometimes that core was a microscopic bit of debris, like the body of a diatom, or a fragment of a seashell. But these cores could also be macroscopic in nature. Frequently when the Challenger crew cracked a nodule open, the center would hold a tooth. Sometimes those teeth were as big as a sailor’s hand. These teeth belonged to the megalodon.6

It’s hard out there for a paleontologist. They need to reconstruct the bodies of long-dead animals using only the parts of those animals that are sturdy enough to stick around for thousands or millions of years. That might seem straightforward when you’re looking at a fully reconstructed dinosaur skeleton in the natural history museum, but that’s only because we don’t know what we don’t know. For instance: If elephants went extinct a million years ago, and we only knew them by their skeletons, we would have no idea about their enormous, floppy ears, or their long, prehensile trunks. And what kind of elephant would that be?

The situation is even more dire when it comes to prehistoric members of the class Chondrichthyes. That’s the taxonomic group that comprises skates, manta rays, stingrays… and sharks. These fish are characterized by skeletons that are cartilaginous, like your ears or nose, rather than bony, like your skull or ribs. And cartilage is a soft tissue that tends to decompose in a matter of weeks, if it doesn’t become a snack for some other fish first.

The shark’s teeth are pretty much the only bits that reliably stick around for any length of time at all. But what shark remains lack in diversity, they more than make up for in quantity.7

Humans grow a set of baby teeth as infants, and the full-size set of 32 pop in a few years later. That second set needs to last the rest of our lives. Sharks, on the other hand, often have five rows of teeth. Sometimes fifteen. The bull shark holds the record, with up to fifty rows of teeth in its mouth! And those chompers don’t have to last very long, either. Sharks are constantly shedding old teeth as rows of new ones move in to take their place.8

With this veritable assembly line constantly pumping out deep-sea dentures, a single shark can grow as many as 50,000 teeth over a 30-year lifespan.9

The megalodon was the largest shark that’s ever lived, stalking the seas during the Miocene epoch until eventually dying out about two million years ago. These guys put the Great White to shame, with a body as long as a tractor trailer and twice as heavy, and jaws that opened more than nine feet wide and could rip a whale in half. Appropriately enough, the name “megalodon” comes from the Greek for “big tooth.”

Other people had discovered megalodon fossils before, but the Challenger expedition uncovered an incredible amount of them. Some of them even appeared relatively fresh, encased in only the thinnest crust of deposited manganese. Could it be that the megalodon never went extinct, but still prowls the murky depths of modern oceans?

That’s not a totally outrageous question. In 1976, the US Navy ship AFB-14 made an unexpected discovery when a megamouth shark got caught in its sea anchor. Despite being a massive animal, it lives in such deep waters that no one had ever seen anything like it.

Even more famous is the coelacanth, a species of fish that was thought to have gone extinct 66 million years ago… until 1938, when museum curator Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer found one for sale among a fisherman’s daily haul in Cape Town, South Africa.

That’s just the kind of historical precedent that keeps hope alive for modern-day cryptozoologists. Those are the people who comb the earth for any evidence that might confirm the existence of living beasts that are either fabulous, like the chupacabra, or long-dead, like the saber-toothed tiger.

The Discovery Channel has leaned headlong into the popular fascination, stoking public curiosity by airing shows like, Megalodon: The Monster Shark Lives in 2013 and Megalodon: The New Evidence the following year. Millions of viewers tuned in to hear how the prehistoric fish could very well still be alive, murdering hapless swimmers off the African coast.

For some reason, a lot of those viewers missed the disclaimer that aired at the beginning of the show, which read,

None of the institutions or agencies that appear in the film are affiliated with it in any way, nor have approved its contents. Though certain events and characters in this film have been dramatized, sightings of “Submarine” continue to this day. Megalodon was a real shark. Legends of giant sharks persist all over the world. There is still debate about what they might be.”

Suffice it to say, these films are entirely bogus. Any scientists who appeared on these programs were either tricked by producers or hired actors. There was considerable backlash from the scientific community, and executives from the Discovery Channel issued heartfelt apologies while wiping their tears with thick wads of advertising revenue.

Megalodon Fever probably reached its apex — or nadir, depending on how you look at it — earlier this year, with Warner Brothers releasing The Meg, an action thriller horror blockbuster in which Jason Statham punches the prehistoric shark to death. The movie holds a 45% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, which is neither high enough to indicate a good movie nor low enough to indicate a fun movie.

All that to say there is basically no debate: The megalodon has been extinct for millions of years. Even those fossils that aren’t encased in thick crusts of manganese are millions of years old — they just didn’t happen to build up a lot of sediment due to environmental factors.

It’s easy to see why this gargantuan killer captures the public imagination, but isn’t it enough to know that such a predator did roam the seas once upon a time? There are so many real monsters in modern oceans that there’s no need to dig up old dead ones. Surely there’s a billion-dollar action movie franchise just waiting to be made about the terrifying tunicate.

At any rate, these weirdly abundant manganese nodules were certainly a curiosity for the Challenger crew, but that was about all. They had stumbled upon what’s certainly the most plentiful source of element 25, but there wasn’t really any need for it in 1872.

Of course, a great deal can change in a hundred years. By the 1970s, the ocean floor was the newest, most exciting frontier in the mining industry. And the pioneer who was going to tackle it was Howard Hughes.

Hughes was one of the most prominent and successful businessmen of the 20th century, but that’s probably the least interesting thing about him. In 1917, at 11 years old, he built the first wireless radio transmitter in Houston, Texas. The following year, he used spare parts from an old steam engine to build a motorized bicycle. As an adult, he entered the nascent film industry, winning an Academy Award for Best Director of a Comedy when he was only 22. He was an accomplished airplane pilot from a young age, setting multiple world records for airspeed, CRASH DESTROYED THREE HOUSES and when World War II broke out, he became even richer as a military contractor.10

If this is all sounding a little bit like Tony Stark, that’s because Howard Hughes was the original genius billionaire playboy philanthropist. Literally. Stan Lee, the comic book luminary who created Iron Man, was fond of explaining the superhero’s origins:

11Given all this, it seemed natural that Hughes’ next venture might involve something like vacuuming precious metals off the ocean floor. A 1973 issue of New Scientist reported excitedly,

On 6 August the vessel Glomar Explorer slipped out of Philadelphia to mine nodules from the ocean floor using techniques more advanced than other companies have even planned. The ship is operated by Summa Inc., an umbrella company for the elusive millionaire Howard Hughes, and was built behind guarded barricades… Hughes has spent $250 million on a new deep sea mining system that observers expect to be able to suck up 5,000 ton per day of manganese, nickel and copper from depths of at least 5,000 metres.12

Pretty impressive stuff! Except for one small thing: the entire story was an elaborate lie concocted by the Central Intelligence Agency.13

A few years earlier, in 1968, the Soviet submarine K-129 went mysteriously missing somewhere in the Pacific Ocean. That’s an unfathomably large area to search for anything, let alone a stealthy submersible.

But the Soviets had to try. There were cryptographic secrets on board that sub… not to mention a handful of short-range nuclear missiles.

The Soviet Navy searched frantically for months, but found nothing. They eventually gave up, but all that commotion had caught the attention of the American intelligence community. They surmised what it was the Soviets had been looking for, and the Americans also had a very helpful tool at their disposal: A vast, global network of undersea microphones called SOSUS, which keeps the oceans under constant audio surveillance. By searching those records, American officials were able to triangulate the position of an underwater implosion — almost certainly the site of the wreck of K-129.

The Americans were desperate to investigate, but there was no way they could just blatantly salvage a Soviet military vessel in international waters. This was the height of the Cold War, and such a transgression could feasibly be provocative enough to turn things hot.14

This is where Howard Hughes came in. Then-National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger explained in a memo:

The determination reached was that deep ocean mining would be particularly suitable. The industry was in its infancy, potentially quite profitable, with no one apparently committed to a hardware development phase and thereby possessing a yardstick by which credibility could be measured… Mr. Howard Hughes… is recognized as a pioneering entrepreneur with a wide variety of business interests; he has the necessary financial resources; he habitually operates in secrecy; and, his personal eccentricities are such that news media reporting and speculation about his activities frequently range from the truth to utter fiction.

So with the cooperation of the “elusive billionaire,” the CIA spent two months in the summer of 1974 in the middle of the Pacific Ocean trying to raise the wreck of the K-129 under the name Project Azorian.15

They succeeded, but only partially. The mechanical grabber accidentally caused more than half of the submarine’s body to fall away, impossible to recover on this mission. So the crew returned to the mainland and started preparing for a second outing, hoping to retrieve what they couldn’t the first time out.

But it appeared that the window of opportunity had closed. Richard Nixon had just resigned, ensuing in the kind of political environment that doesn’t lend itself well to clandestine operations. Even worse, someone had broken into Summa Corporation headquarters and stolen documents revealing the true nature of the Glomar Explorer. Not long after, the story leaked to the press, and the true story was front-page news all across America… and the Soviet Union.

The intelligence community was rather relieved to see that the Soviets were basically too embarrassed by the whole affair to make much of a public stink about it, so they followed suit. When a Freedom of Information Act request was filed, the CIA sought to refuse the release of any documents in the most anodyne way possible. The solution: Some creative agent responded that the CIA could “neither confirm nor deny” any connection with the Hughes Glomar Explorer, a now-classic phrase whose use has far outlived the infamy of this particular incident.16

Ultimately, a second expedition was completely out of the question. The Soviet Navy started camping out at the site of the wreck, and may have conducted their own salvage operations.

The total cost of Project AZORIAN was around $800 million, or about $3 billion in 2018 dollars. It didn’t result in much useful intelligence, and Howard Hughes’ legacy is stuffed so full of outrageous scandals that this single bizarre episode isn’t enough to overshadow all that. As for the Glomar Explorer? It was eventually converted into a deep-sea drilling ship, but only operated for a few years before it was scrapped in 2015. It never did harvest a single nodule of manganese off the ocean floor.

Pretty much nobody else has, either, which means there are still plenty of ’em down there, just waiting for a rush of element collectors. Plus, you can crack them open in hopes of finding a fossil, like some kind of paleontological Kinder Surprise.

Our bodies do require manganese in extremely small amounts, and the best dietary sources of Element 25 include vegetables like sweet potatoes and beets, as well as escargot. But you don’t want to go too hog wild on those French snails: Overexposure to the substance can lead to a permanent neurological condition called, no joke, “Manganese Madness.” Admittedly, this tends to be more of a problem for workers in the mine shaft, rather than patrons of fine dining establishments.17

Our own extinct cousins, the neanderthals, happened to be avid collectors of manganese. They would use the deep purple oxide to paint their faces. This recent discovery has helped advance the notion that contrary to popular opinion, neanderthals were quite capable of symbolic thinking, and were probably actually quite clever.

That’s not even the most impressive painting prehistoric humans performed. Occasionally, they would take one of those sticks of manganese and apply it to a cave wall, creating beautiful renditions of animals and other people. The most famous of these paintings is in Lascaux, France, where images of hunters, horses, and bulls have adorned the rocky walls for over 15,000 years.

So if you’re trying to put together a display of the elements that’s designed to impress, you’ve been warned: the bar is set pretty high.

Thanks for listening to The Episodic Table of Elements. Music is by Kai Engel. To learn… visit episodic table dot com slash M n.

Next time, we are going to pump you up with iron.

This is T. R. Appleton, reminding you that sharks have far more reason to be afraid of you than you have to be afraid of them.

Sources

- Chemicool, Manganese Element Facts. Dr. Doug Stewart, October 7, 2012.

- Warwick Research, Lignin Degradation.

- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, History Of Oceanography.

- Encyclopedia.com, Deep-Sea Exploration: The HMS Challenger Expedition. 2001.

- Interactive Oceans, The Voyage Of The HMS Challenger.

- The Geological Society, Treasures Of The Abyss. Geoff Glasby.

- Fossil Guy, Types Of Shark Fossils.

- Today I Found Out, Can Sharks Really Grow An Unlimited Number Of Teeth? Karl Smallwood, April 17, 2017.

- USCB ScienceLine, How Many Teeth Is A Shark Supposed To Have? March 16, 2011.

- History.com, 7 Things You May Not Know About Howard Hughes. Elizabeth Nix, July 7, 2015.

- Stan Lee on Iron Man.

- New Scientist, Ripping Off The Ocean Bed. Technology Review, August 16, 1973.

- io9, That Time The CIA And Howard Hughes Tried To Steal A Soviet Submarine. Mark Strauss, April 10, 2014.

- Signature Reads, That Time Kissinger Kept Project Azorian From Killing U.S.-Russia Relations. Josh Dean, September 11, 2017.

- Popular Mechanics, 5 Things About America’s Daredevil Mission To Salvage A Soviet Nuclear Sub. Andrew Moseman, August 29, 2017.

- U.S. Department Of Justice, FOIA Update: OIP Guidance: Privacy “Glomarization”. January 1, 1986.

- Nature, Manganese The Protector. John Emsley, October 24, 2013.